Thread

Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany is one of the world's most famous and beautiful castles.

But it isn't a real castle: it has central heating, hot water, flushing toilets, telephones, and elevators.

Because Neuschwanstein is actually the world's biggest work of fan fiction...

But it isn't a real castle: it has central heating, hot water, flushing toilets, telephones, and elevators.

Because Neuschwanstein is actually the world's biggest work of fan fiction...

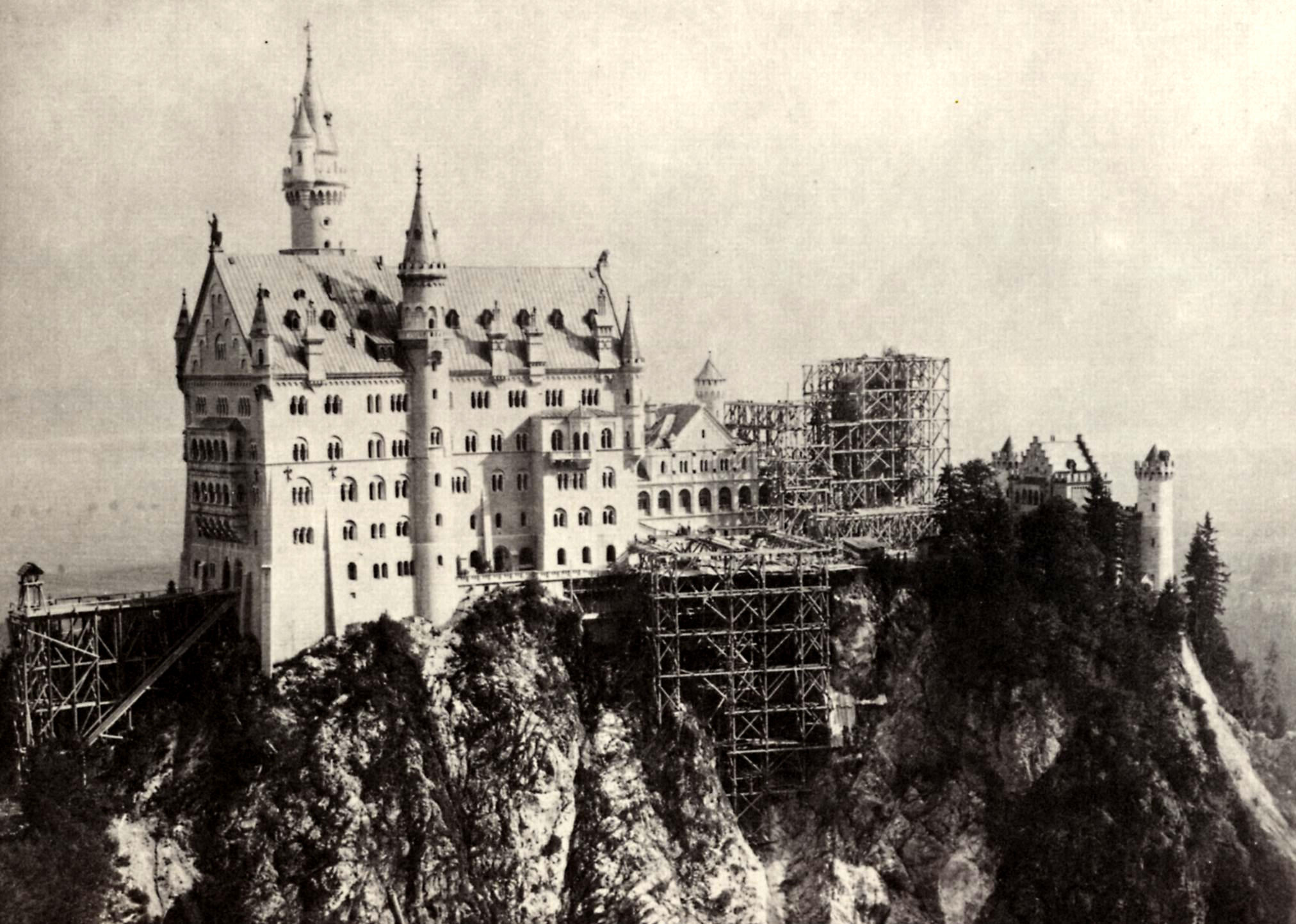

Neuschwanstein Castle was started in 1869 by King Ludwig II of Bavaria (and never finished).

So it isn't a Medieval castle at all, but a 19th century facsimile; not a defensive fortification but a residential palace for a king.

No knights ever lived here.

So it isn't a Medieval castle at all, but a 19th century facsimile; not a defensive fortification but a residential palace for a king.

No knights ever lived here.

Why did Ludwig build Neuschwanstein?

Well, Ludwig was an eccentric king. He came to the throne in 1864 and took no interest in politics. He left the business of running the state to his cabinet of ministers and spent all his time on the things he truly cared about.

Well, Ludwig was an eccentric king. He came to the throne in 1864 and took no interest in politics. He left the business of running the state to his cabinet of ministers and spent all his time on the things he truly cared about.

What interested Ludwig was art, literature, architecture, poetry, and music; it had been that way since he was young, growing up as a lonely child in Hohenschwangau, itself a neo-Gothic castle built by his father, King Maximilian.

In his solitude he turned to art.

In his solitude he turned to art.

It was near this castle, nestled in the leafy mountains of southern Bavaria, that Ludwig built Neuschwanstein, which he wanted to be an even more fantastical and faithful vision of Medieval Romance than Hohenschwangau.

But where did he get all these fanciful ideas?

But where did he get all these fanciful ideas?

Ludwig had first seen the operas of Richard Wagner when he was a teenager.

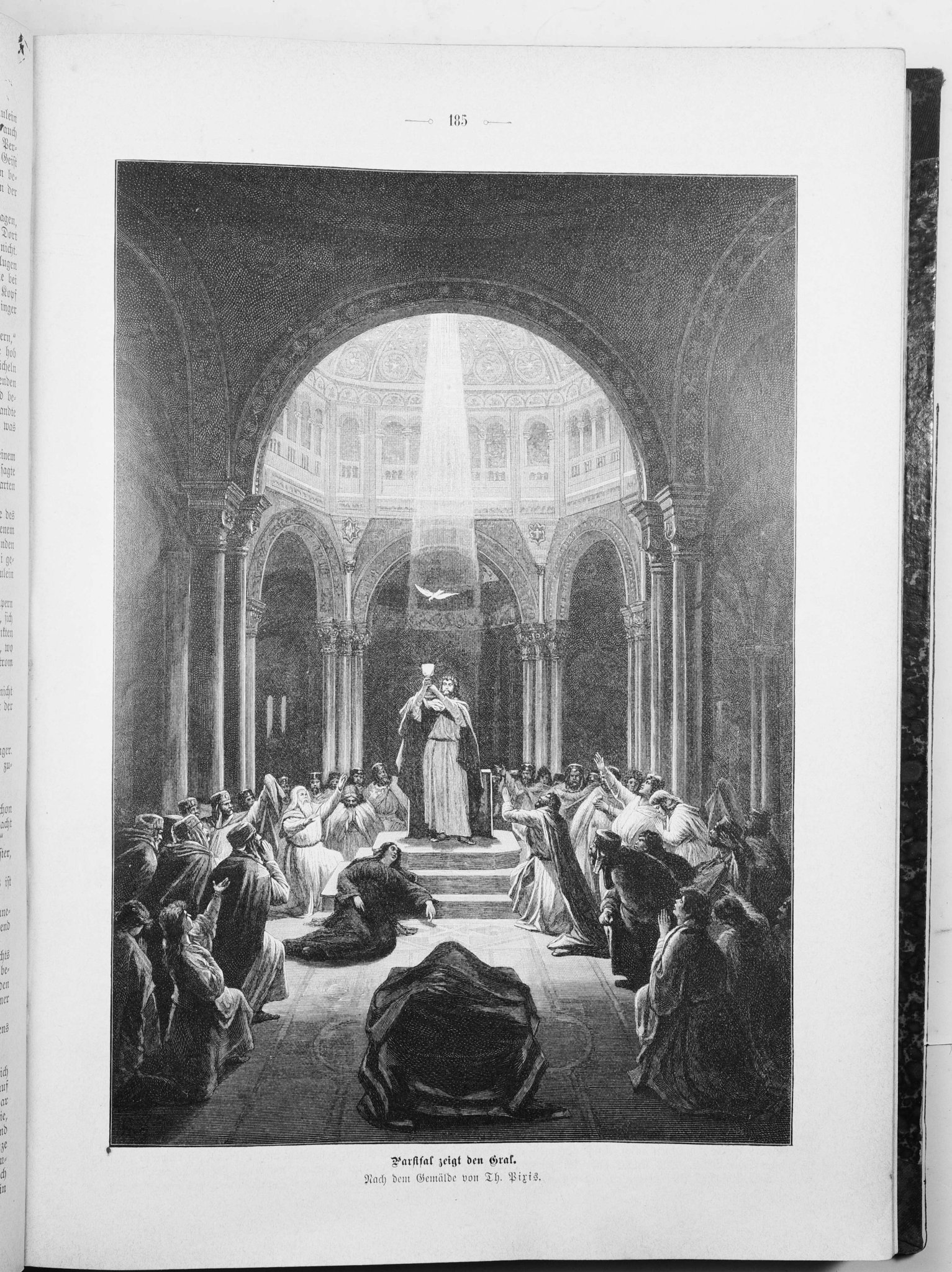

Parsifal, Lohengrin, Tannhauser - these operas told stories from the myths of Medieval Germany: knights and maidens, castles and wizards, great quests and romances.

Ludwig fell in love with them.

Parsifal, Lohengrin, Tannhauser - these operas told stories from the myths of Medieval Germany: knights and maidens, castles and wizards, great quests and romances.

Ludwig fell in love with them.

When he was king Ludwig became Wagner's primary artistic patron, supporting his work and even helping him to build his own opera house - without Ludwig there would probably be no Wagner to speak of.

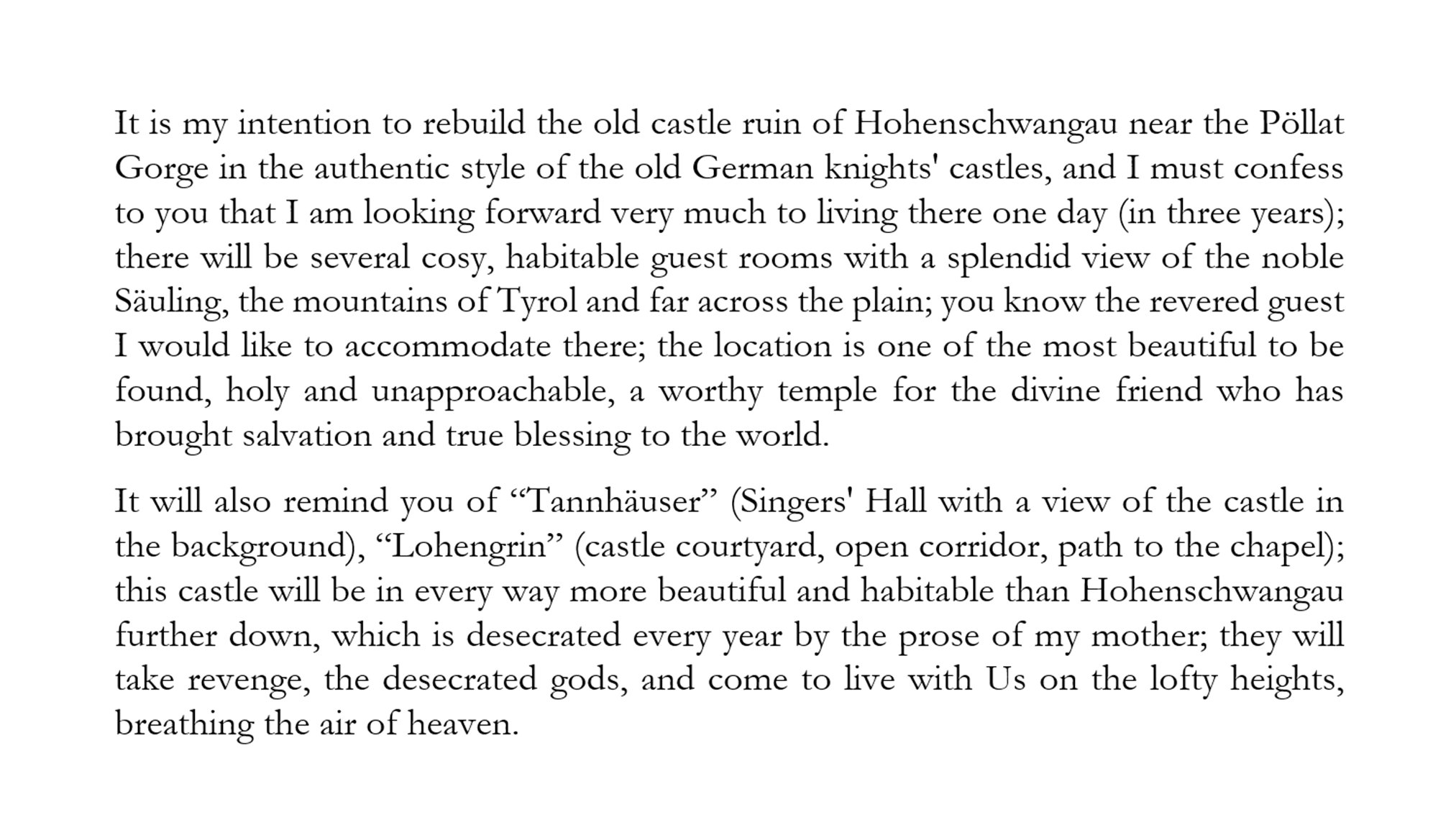

In a letter to Wagner Ludwig explained his ambitions for Neuschwanstein:

In a letter to Wagner Ludwig explained his ambitions for Neuschwanstein:

And so Neuschwanstein was both Ludwig's testament to Wagner, the greatest composer of the age, and a way of realising the Romantic Medieval fantasies which had filled his head since he was a child.

Hence why the rooms of the castle are decorated with paintings depicting scenes from German legend as told by Wagner: Parsifal in the Singers’ Hall, Tannhäuser in the study, and Lohengrin in the parlour.

This was Ludwig's love letter to Medieval Romance.

This was Ludwig's love letter to Medieval Romance.

Parts of it were even directly modelled on the operas of Wagner and the stage directions he had written.

Like the Hall of the Holy Grail, a neo-Byzantine spectacle based on a hall of the same name in Wagner's Parsifal.

Like the Hall of the Holy Grail, a neo-Byzantine spectacle based on a hall of the same name in Wagner's Parsifal.

Of course, Ludwig had Neuschwanstein installed with running water, flushing toilets, elevators, telephone lines, and all the other conveniences of modern life - this was going to be his home.

Critics at the time called it artificial, sentimental, ostentatious, and inauthentic.

Critics at the time called it artificial, sentimental, ostentatious, and inauthentic.

Perhaps those critics were right. And yet for over a century Ludwig's architectural fantasy has been delighting people around the world.

People often describe Neuschwanstein as a "fairytale castle" - that's *exactly* what it was always supposed to be.

People often describe Neuschwanstein as a "fairytale castle" - that's *exactly* what it was always supposed to be.

And it wasn't without precedent; there was a fashion in Europe for building neo-Medieval castles.

Ludwig himself had visited some of them, such as Hohenzollern, Lichtenstein (which was inspired by a novel), and the Château de Pierrefonds.

Ludwig himself had visited some of them, such as Hohenzollern, Lichtenstein (which was inspired by a novel), and the Château de Pierrefonds.

Nor was Neuschwanstein Ludwig's only fantastical project. He also built the Herrenchiemsee Palace on an island in the middle of Bavaria's largest lake.

This one was inspired by the Palace of Versailles and even has its very own hall of mirrors.

This one was inspired by the Palace of Versailles and even has its very own hall of mirrors.

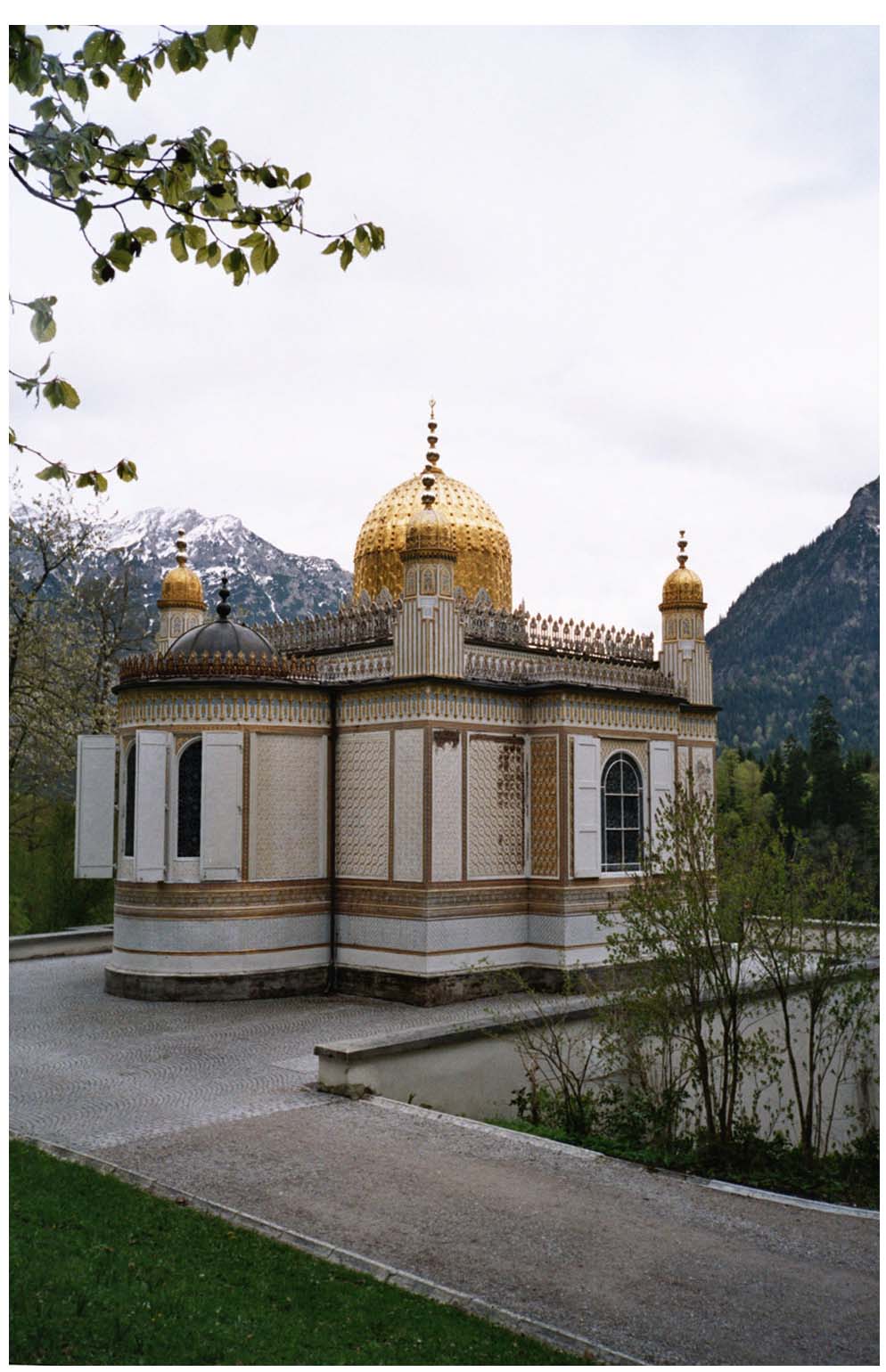

And then there's the Linderhof Palace, again inspired by 18th century French architecture rather than by Medieval fantasy.

Its grounds include a "Grotto of Venus" with technicolour lighting and a group of follies inspired by Moorish architecture.

Its grounds include a "Grotto of Venus" with technicolour lighting and a group of follies inspired by Moorish architecture.

Toward the end of his reign Ludwig withdrew completely from any royal or political engagements.

He became something of a recluse, dedicating all his time and money to these architectural fantasies; he even had plans for Byzantine and Chinese palaces that never came to fruition.

He became something of a recluse, dedicating all his time and money to these architectural fantasies; he even had plans for Byzantine and Chinese palaces that never came to fruition.

Ultimately Ludwig's disinterest in politics and his huge personal expenses, which had left him deeply in debt, precipitated his end.

Ludwig's ministers had him declared insane, after which he was arrested at Neuschwanstein and deposed, to be replaced as king by his uncle.

Ludwig's ministers had him declared insane, after which he was arrested at Neuschwanstein and deposed, to be replaced as king by his uncle.

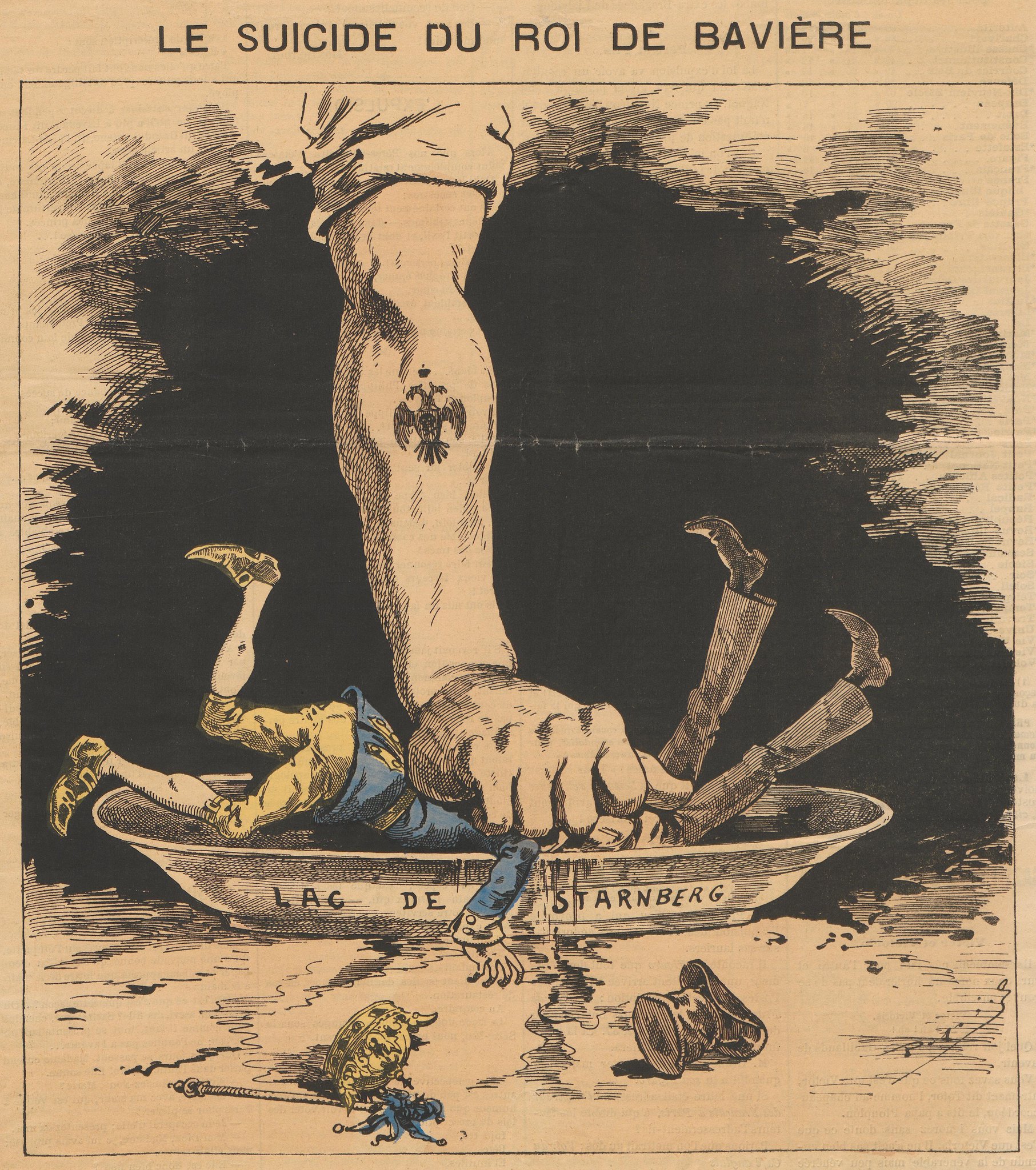

Two days later Ludwig drowned while taking an evening walk with the psychologist Bernhard von Gudden near Berg Castle, where he had been taken.

The circumstances of his death are shrouded in mystery. Officially it was suicide; many, even at the time, suspected murder.

The circumstances of his death are shrouded in mystery. Officially it was suicide; many, even at the time, suspected murder.

The original plans for Neuschwanstein were simplified and its exterior completed by 1892; the rest, including many of the rooms, were never finished.

And, alongside the Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee, it was opened to the public almost immediately after Ludwig's death.

And, alongside the Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee, it was opened to the public almost immediately after Ludwig's death.

So what do we make of Ludwig? His life was, in some ways, rather tragic.

And as for his fantastical building projects, do they deserve to be praised or mocked? Admired for their ambition or criticised for their extravagance and inauthenticity?

And as for his fantastical building projects, do they deserve to be praised or mocked? Admired for their ambition or criticised for their extravagance and inauthenticity?

It's hard to say. Ludwig had seen the great architecture of other nations and wanted to give his native Bavaria a similar cultural heritage to be proud of.

And that he certainly did; Neuschwanstein, even if it isn't "real", is one of the most visited castles in the world.

And that he certainly did; Neuschwanstein, even if it isn't "real", is one of the most visited castles in the world.

And the huge sums Ludwig spent on his palaces - all from his personal fortune, never from public funds - were used to employ local labourers, craftsmen, and other workers, and brought money into what were otherwise rural and fairly impoverished communities.

All of this explains why, even if politicians and high society didn't like him, the people of Bavaria loved Ludwig.

He was known for taking walks around the country, talking to farmers or fishermen, and his great building projects seemed to be for them as much as for him.

He was known for taking walks around the country, talking to farmers or fishermen, and his great building projects seemed to be for them as much as for him.

Mentions

See All

Amjad Masad ⠕ @amasad

·

Mar 20, 2023

Very interesting thread.