Thread

Very good question. I would however separate it to two different topics:

1. Why was the Russian army so much overrated?

2. Why was the Ukrainian army so much underrated?

Let's try to briefly discuss both. This is far from a complete answer however🧵

1. Why was the Russian army so much overrated?

2. Why was the Ukrainian army so much underrated?

Let's try to briefly discuss both. This is far from a complete answer however🧵

First of all, saying that analysts failed to see the hollowness of the Russian military might be an overgeneralisation. Some noticed some aspects of that hollowness. Here is a brilliant analysis of a Russian westward invasion scenario from the Nov 2021

warontherocks.com/2021/11/feeding-the-bear-a-closer-look-at-russian-army-logistics/

warontherocks.com/2021/11/feeding-the-bear-a-closer-look-at-russian-army-logistics/

I like this article very much. In my opinion, it correctly grasped two particular features of the Russian army:

1. It is a land-based army with *lots* of artillery & air defence (=consumes a lot)

2. Its supply lines are fragile, overwhelmingly relying on the railway network

1. It is a land-based army with *lots* of artillery & air defence (=consumes a lot)

2. Its supply lines are fragile, overwhelmingly relying on the railway network

If Russian army is artillery-based, thus requiring a steady supply of bulky ammunition, but its logistics forces are weak and don't really allow it to get far away from the railway network, than the adversary must retreat and draw the Russians further from their supply depots

Technically Vershinin discussed scenarios of Russian invasion in Poland or the Baltic States. But let's be honest, in Nov 2021 another scenario looked way more plausible. Without naming Ukraine, the author correctly identified the Russian weakness and suggested how to exploit it

I gave an example of what I consider to be a great analysis. Vershinin correctly grasped the land-based artillery-centric character of the Russian army and its logistical weakness in operating far away from its own railroads. And gave correct policy recommendations

Now let's think in higher orders. What exactly did the author grasp correctly? First of all, it is the material side of the army, its "hardware". His analysis relies on objective, verifiable and quantifiable criteria. That makes his argument far more difficult to criticise

What kinds of sources is Vershinin using? He relies on what a historian would call "secondary sources", someone else's studies. That's fine. But those secondary sources in their turn rely on some primary sources. What types of sources on the Russian army do they rely on?

Russian theorist of history Lappo-Danilevsky classified primary sources into two categories:

1) Myths

2) Remnants

Let's say a chronicle narrative about a military expedition is a myth. But the account journals from the same expedition would be remnants

1) Myths

2) Remnants

Let's say a chronicle narrative about a military expedition is a myth. But the account journals from the same expedition would be remnants

"Mythical" info is something that its authors deliberately intended to tell us. To the contrast, "remnant" info is something that was created without a specific intention to convey a message to the audience. Chronicle vs an account journal. A big difference

Now there is a paradox. The same artefact can serve either as a myth or as a remnant depending on how we use it & which data we draw from it. If we draw the data they wanted to give us, it's a myth. If we draw the data they didn't intend to give (but still did), that's a remnant

The most obvious example could be a slip of the tongue which is often more reliable than the central claim. Let me give you a simple example. A Soviet WWII veteran is talking of a training centre where he was sent as a recruit before being shipped to the frontline as a soldier

An interviewer asks:

- How did they feed you there?

- Very well

Then veteran forgets about it. But in 10 minutes he recalls a story. Once they were having a lunch, while the formation signal sounded. Everyone had to leave their food and run outside to make a formation

- How did they feed you there?

- Very well

Then veteran forgets about it. But in 10 minutes he recalls a story. Once they were having a lunch, while the formation signal sounded. Everyone had to leave their food and run outside to make a formation

Bit sad, innit? But this soldier filled pockets of his coat with porridge and then finished it during the day. "Damn, you are smart" his comrades said

Central claim = we were fed well (myth)

Unwanted slip of the tongue = we were starving (remnant)

Know the difference

Central claim = we were fed well (myth)

Unwanted slip of the tongue = we were starving (remnant)

Know the difference

This analysis, which is correct, brilliant and most importantly useful, ultimately relies on the myth-information. And it is good enough (in this case). Because you indeed can draw lots of correct info about the Russian military machine from the Russian sources directly

And yet, even though a method of directly open sourcing the data from the myth-sources can work, it's not universal. In many cases it won't work out. I would even argue that in some (important) cases, high-quality secondary sources just won't be available for the public use

That doesn't mean that there is a universal conspiracy about hiding this information. Not at all. To the contrary, some actors or institutions might have absolutely intended to:

1) make a study

2) publish its results

But something didn't work out

1) make a study

2) publish its results

But something didn't work out

In one (purely hypothetical) scenario a Russian industrial company has ordered a study to a group of researchers intending to publish a pdf on its own web site. But upon getting the final results, CEO decided not to publish anything

In another, even more hypothetical scenario, results of a study were published. But a certain state security (not necessarily Russian) intervened and they were deleted. Moreover, participants were incentivised not to disclose anything

I gave only a couple of hypothetical examples of why high quality aggregated data may be unavailable for the public use, when powerful actors don't want it to be. Which means you can't open source it by simply downloading a paper from the website and using it as a source-myth

What you can do is:

1) take lots of pieces absolutely available data

2) use them as sources-remnants (look at what they did *not* want to say, but still did)

3) aggregate

Soon I'll publish an longread, showing how classified info can be drawn from totally unclassified sources

1) take lots of pieces absolutely available data

2) use them as sources-remnants (look at what they did *not* want to say, but still did)

3) aggregate

Soon I'll publish an longread, showing how classified info can be drawn from totally unclassified sources

Now why don't we see more examples of such approach? Well, for a number of reasons. I'll focus on the most important one. To launch such project you need to start with a correct question. And to ask a correct question you need to know half the answer. You need specific knowledge

An interesting thing about the Vershinin's approach is that it is universal. His methodology can technically be applied anywhere. It's not only model-centric, but even more importantly universal-model-centric. And it worked (this time). But you necessarily leave a lot aside

And what do you leave out? Specific knowledge. Specific to this or that area, nation, culture. And "culture" here should be understood much more broadly than "arts&entertainment". You leave out their patterns of thinking and of action. You leave out their memes

"Independency" of human thinking and action is in my opinion hugely overrated. Independent thinking and action is costly. Thus in most cases we don't really think much. We just use theoretical and practical tools that are already popular in our (broadly understood) culture

Both theoretical and practical tools are instruments we use for solving our problems. Therefore, the range and the character of instruments we have defines which problems we can address and how we can address them. If we have only a hammer, we will treat everything as a nail

One brilliant idea I borrowed from @Noahpinion is that a major factor of the East Asia economic miracle was the Georgism of the US economists sent there after the WWII. Georgist-trained economists had only Georgist tools and applied them everywhere. Accidentally, they were right

To the contrast, economic catastrophes over much of the post-Soviet space seem to be influenced by the neoliberalism of the Western economic mainstream of the 1980s. These guys had only neoliberal tools and applied them everywhere. Accidentally, they were wrong

Our actions and their results depend on what theoretical and practical tools we have. We are neither smart, nor informed enough to verify the assumptions those tools are based on. Realistically, we can only apply the tools we have, and hope our assumptions were correct

It is important to understand that different institutional cultures use different sets of instruments, based on different sets of assumptions. Whatever instruments they use, very much determines what they can do and how

Currently I am puzzled by the following question. Can the members of the US institutional culture correctly identify sets of theoretical and practical tools other institutional cultures are operating with? I am not sure, what the answer would be

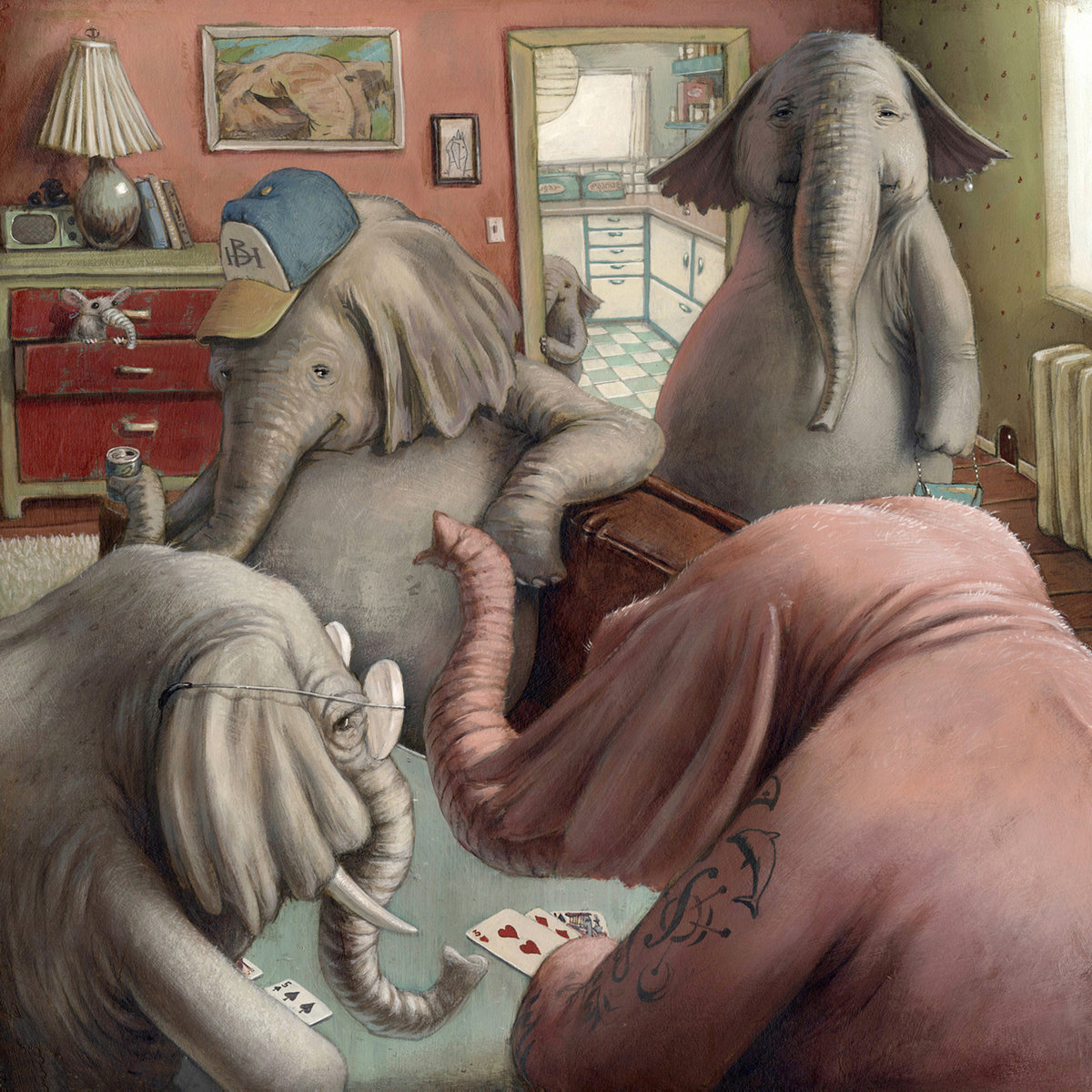

I am pretty sure that the American expert community misjudges the Russian intellectual culture. Focusing on unimportant & irrelevant (though cool & quotable) stuff they miss a herd of elephants in the room. Individual experts know they exist but the expert community doesn't

Let me give you an example. When the KAMAZ truck producer was planning its IPO, its managers hired consultants to plan their strategy. But it wasn't BCG or McKinsey. They outsourced their planning to an esoteric (not spiritual, more "scientific" sect)

This isn't a separate example. The same sect has long provided consultant services first for individual businessmen, then to corporations and finally for politicians (which, reportedly was the most pleasant and rewarding of all). It's well-known in Russia, but not beyond

Now you may ask why this topic (which has *tons* of publications on in Russian) has nearly zero coverage in the West. Well, because to understand why it's happening you need to put it into the context of the Russian culture. Only then it will make sense

Sartre taught us that "Hell is others". I could add that "Dumb is others". Lots of stuff we are doing makes total sense within our culture, but sounds absolutely dumb for an outsider. Like an esoteric movement providing a truck producer with the unironically valuable expertise

Many phenomena of an alien culture sound incredibly dumb when put out of context. And that's why they are ignored. Discussing something truly dumb or even worse studying it professionally, you may lose your status. And dumb here means = decontextualised

That creates a huge bias towards everything high-brow across areas studies. And the "high-brow" would mean: "something recognisable and relatable to sweet ourselves". Everything unrelatable (=truly specific to the culture) gonna be ignored. I see it often in the Russian studies

If what I described above is true, that might explain why actions and practices of Russia look so "crazy" or "irrational". Let's assume for the sake of the argument that they are super rational from the perspective of the framework that Kremlin intellectuals are operating with

Let's assume that "irrational" or "dumb" means simply "decontextualised". So let's contextualise the Russian behaviour. Let's assume that we ignore a herd of elephants in the room because we find them unrelatable and thus noticing them would decrease our status in the community

I'll try to start. In my next thread I'll outline some considerations regarding the origins of Z-letter as the new Russian symbol. That's just an educated guess, nothing more. Still, some might find it valuable. End of 🧵

Let's make a summary to the yesterday's🧵

Failure to grasp the hollowness of the Russian military largely resulted from the over concentration on its "hardware". Which is objective, quantifiable, verifiable. Hardware-focused studies sound less objectionable and thus are incentivised under the vetocracy

Much less focus was made on the "software" of the Russian military. Its institutional culture (which is now *shockingly* anti-intellectual), its internal system of incentives, its role within the broader socio-political system. Its relations with other agencies (FSB, FSO)

While I could give examples of great analyses focused on the "hardware" of the Russian military - and started with the one that aged especially well - I can't recall any "software" analysis of it that I could truly recommend. Software-focused, culture-specific, remnants-based

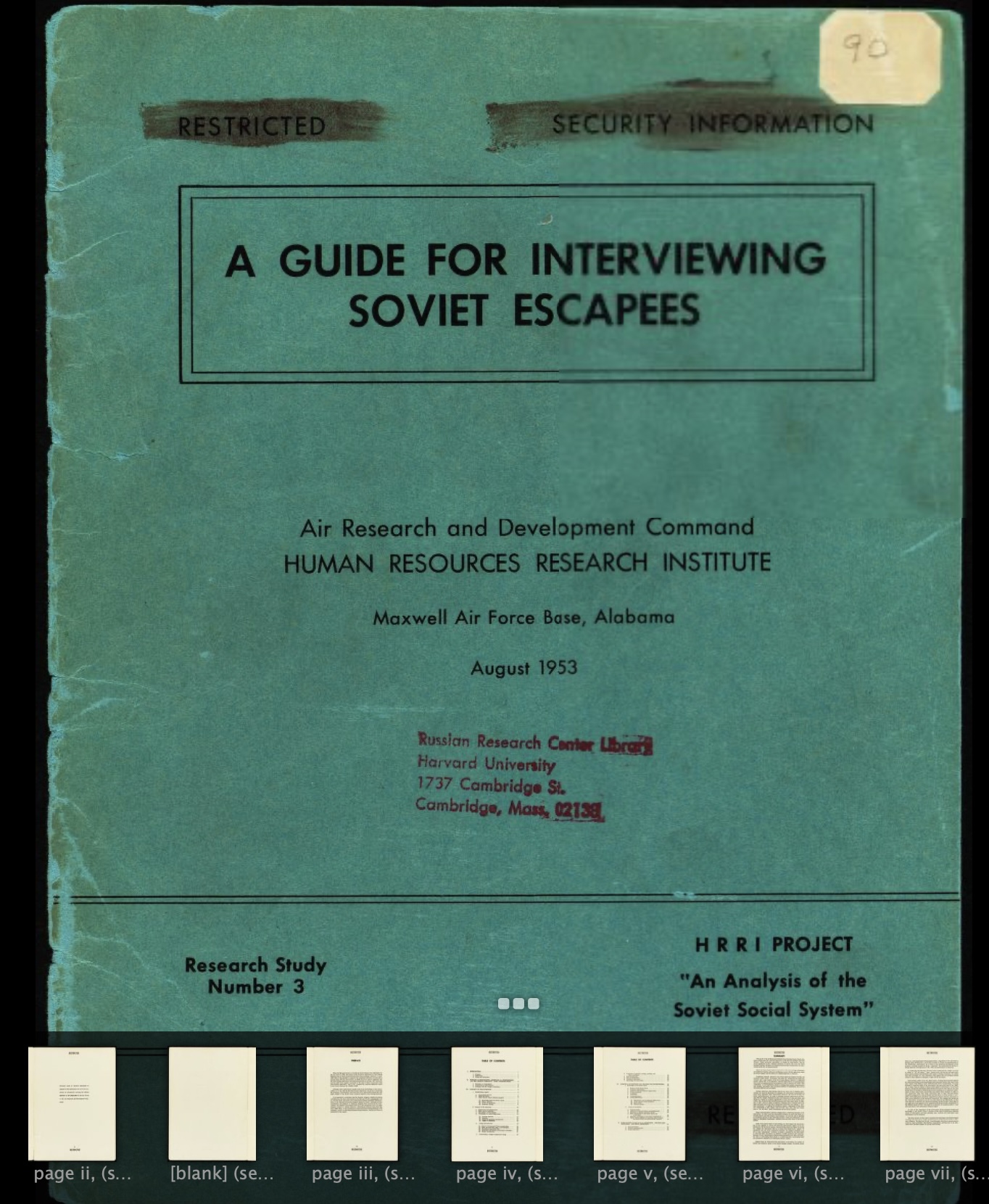

Interestingly enough, in the past US military used to be interested in such software-focused, culture-specific, remnants-based studies. Consider The Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System Online commissioned by the US Airforce in 1950 library.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/static/collections/hpsss/index.html

Within the Harvard Project they interviewed over 700 refugees from the USSR to paint a broader picture of the Soviet society. And they treated the testimonies as remnants. What impressed me when studying this project, was its remnants-perspective and the lack of wishful thinking

For example, most refugees bashed the Stalin's regime and often claimed it has very little popular support. They might have hoped that would help them immigrate to the US, or to whitewash themselves from the Soviet past, or they simply gave that answer to please the interviewers

Unbelievably it may sound, they fooled no one. The manual explicitly stated that refugees "may distort their answers in order to tell Americans what they think Americans want to hear" partially from desire for approval, partially to increase their chances in the non-Soviet world

Let me give you some quotes to illustrate the manual's general attitude. Here for example they correctly mention that the refugees may fear to disclose both their pro-Communist (black spot for immigration security) and anti-Communist (aren't you a fascist?) activities

The manual argues that the differences between the American and the Soviet system are so great, that you can't judge the plausibility of information you are getting based on your "common sense". Sounds good, doesn't work. Many unbelievable stories were later proven very plausible

Most importantly. An interviewee is not your projection. It's not an anti-American who should put you on guard but rather the one "who comes up with an air-tight story and appears to be completely and unequivocally sympathetic to the Western point of view". That is very unnatural

Once again, US interviewers of 1950 didn't perceive interviewees as their projections. They realised they're members of another culture with different experience and perspective. If they're too pro-Western and their stories make too much sense, that should alarm the interviewer

Interviewees were perceived as people with agency and their own goals. Of course they will try to please the interviewers to whitewash themselves, to get an approval and to increase their chances in non-Soviet world. They'll make up a story they think interviewers want to hear

Whereas most interviewees criticised the Soviet regime and often painted a picture of a purely violence-driven system which has little or no popular support, the study concluded that Stalin's regime has a wide popular support in the USSR. They treated testimonies as remnants

Can the modern US expertocracy produce anything comparable to the Harvard project of 1950? I'm not so sure. For a number of reasons I don't think that that level of intellectual integrity, humility and surprising lack of wishful thinking can be achieved nowadays

I would argue that the US would have *way* better understanding of the modern Russian military if they conducted something comparable. Like Interviewing a 100 of former Russian officers and soldiers, treating their testimonies as remnants and later aggregating them

If such a project had been conducted and conducted properly, it would improve the understanding of the Russian military "software" tremendously. I don't think that the US expert community has an adequate understanding of that institutional culture and its structure of incentives

Whereas the capacities of the Russian army had been hugely exaggerated, the capacities of the Ukrainian one had been just as hugely underrated. Why? Well, once again, they missed the "software" aspect of the Ukrainian military. Culture, values, incentives. Identity

On the one hand, painful and humiliating defeats of 2014 triggered the institutional evolution as they often do. Retrospectively speaking, making some painful blows on Ukraine but not finishing it, Putin made a major mistake. It evolved and its military evolved, too

If you consider the inner structure of Ukrainian military and the state machine, it makes total sense. A painful defeat and existential threat often spark the institutional evolution, because they change the system of incentives, of rewards and punishments

All large organisations suffer from the problem of attribution which heavily skewes their systems of rewards and punishments. Honestly speaking, under normal circumstances high performers are ostracised, pushed out or destroyed. That's how it should be

As a general rule, a large organisation suffering from the problem of attribution can start rewarding high and extremely high performance only if the organisation feels an immediate existential threat. Which happened in Ukraine after 2014. Fear changed the system of incentives

After 2014 Ukrainian identity evolved just as much as its army. In 2012 East and South Ukraine was very Russian. By 2022 it was very anti-Russian. This change of attitude resulted not so much from the war per se as because of what happened in Donbass under the Russian rule

When manufacturing the Donbass catastrophe in 2014, Putin correctly realised that the story about "civilians being shelled by Ukrainian Nazis for years" would give him a casus belli both in the eyes of the Russian nationalists and in the eyes of the Western useful idiots

What he didn't realise however was that the Russian-ruled Donbass would become the showcase of the "Russian world" in the eyes of Ukrainians. In 2014 many believed that Russian rule could bring some benefits. By 2022 nobody believed that except for some geriatric pensionaries

This change of software heavily impacted the "hardware" aspect of the war such as its logistics. Wild stories about Russian columns being stuck in the Ukrainian fields with no fuel make more sense, if we consider that they expected the locals to supply them with it. Surprise

It seems to me that the US expert community systematically disincentivizes studying the "software" aspect of the Russian military. This however, creates a big problem for analysing its "hardware" as well. Because the two are in fact indivisible

Within a week or two my team will publish a long read which will integrate both the software and the hardware approaches. It will be narrow-focused and focused on a certain bottleneck of the Russian military machine that received very little coverage so far. End of 🧵

Mentions

See All

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Nov 28, 2022

- Curated in Russia Invades Ukraine

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Jul 20, 2023

- Curated in Russia's 2014 Invasion of the Donbas