Thread

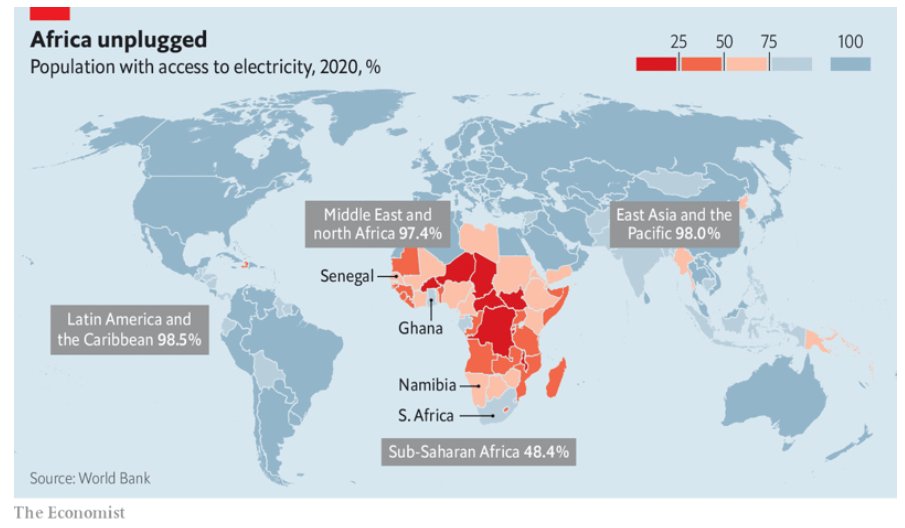

"Average electricity consumption per person in sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa, is a mere 185 kWh a year, compared with 6,500kWh in Europe and 12,700kWh in America"

@johnpmcdermott & me in @TheEconomist on #energy & #climate in #Africa🧵(1/n)

www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/11/03/africa-will-remain-poor-unless-it-uses-more-energ...

@johnpmcdermott & me in @TheEconomist on #energy & #climate in #Africa🧵(1/n)

www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/11/03/africa-will-remain-poor-unless-it-uses-more-energ...

Low energy use is a consequence of poverty; but it is also a cause of it. If Africa is to grow richer it will need to use a lot more energy, including fossil fuels. Yet its efforts to do so put it on a collision course with hypocritical rich countries. (2/n)

The rich world is happy to import fossil fuels for its own use, while at the same time restricting public financing for African gas projects intended for domestic use “Is the West saying Africa should remain undeveloped?” fumes Matthew Opoku Prempeh, Ghana’s energy minister (3/n)

To be sure, clean-energy technologies are a huge opportunity for the continent. They are already the main sources of power for 22 of Africa’s 54 countries. But to hope that Africa can rely on renewables alone to boost consumption is naive. (4/n)

Many businesses and well-off households rely on generators. These have more total capacity than there is in sub-Saharan Africa’s installed renewables. (5/n)

To reach universal energy access by 2030 the IEA thinks that total capital spending on energy between 2026 and 2030 in Africa would have to be nearly twice what it was between 2016 and 2020. Investment in clean energy would need to rise six-fold. That is highly ambitious.(6/n)

Governments in rich countries have promised climate finance that, among other things, is meant to encourage private investment in renewables. The IEA calculates some $1.2trn will be needed by 2030. Yet the past is filled with broken promises. (7/n)

In 2009 rich countries pledged $100bn a year to poor countries by 2020 to help with climate change (some of it from the private sector). But the annual amount has never surpassed $85bn and much of it has been in the form of loans. (8/n)

One reason private investment is low is struggling utilities. More than half of those in sub-Saharan Africa cannot cover their operating costs—let alone fund investments. (9/n)

In the ten years to 2021 about two-thirds of new generation capacity in Africa came from gas-fired stations. Even if African countries invest heavily in renewables, many will still need an on-demand source of electricity to cover the vagaries of the weather (10/n)

Hydropower can help, but only in places blessed with steep valleys and rivers. And gas remains hard to beat for directly powering heavy industry. (11/n)

Happily, in much of the continent renewables are already cost-competitive with gas and coal. By 2030 they should be more so. Better and cheaper batteries could eventually help renewables cope more easily with peak demand. (12/n)

But for now, in places with abundant gas reserves, little hydropower potential or frequent outages throughout the day, gas-fired plants may still offer the most compelling combination of flexibility, stability and price—at least for some new generation (13/n)

Yet last year 39 countries and organisations including almost all of the world’s big, rich democracies—call them the Virtue-signalling 39, or v39—pledged to stop almost all financing of new fossil-fuel projects internationally by the end of the year (14/n)

The hypocrisy is easy to spot: three-quarters of the European members of the v39 are building new fossil-fuel pipelines at home. (15/n)

Gas exploration and development are largely financed by private firms, so the ban will not stop gas being found and pumped. But it will ensure it will be mainly rich countries (including members of the v39) that get to burn it. (16/n)

Africans are understandably angry. Consider a thought-experiment in which sub-Saharan Africa (excluding already higher-consuming South Africa) increases its electricity consumption per head overnight by an extraordinary factor of five. (17/n)

That would give it a level of electricity consumption per person akin to that of Indonesia today—a scarcely conceivable transformation for ordinary Africans and one which took Indonesia almost three decades to achieve. (18/n)

Even if all the new electricity came exclusively from gas-fired power stations (which no one is suggesting), these would add the equivalent of about 1% of current global emissions. (19/n)

For much of Africa the best way of adapting to a warming planet is to become rich enough to deal with its consequences. Denying Africans cheap and reliable power will make this task much harder, while doing almost nothing to curb global warming. (20/20)

Mentions

See All

Roger Pielke Jr. @RogerPielkeJr

·

Nov 4, 2022

Excellent 🧵 & article