Thread

101 tweets about 100 books from my shelves.

~4 per day chosen from a different section, I can do it!

my rules: fiction and non-fiction, must have been read, avoid things from my "Best Books on Everything" thread.

Feel free to ask follow up questions!

@threadapalooza #TPLZ21

~4 per day chosen from a different section, I can do it!

my rules: fiction and non-fiction, must have been read, avoid things from my "Best Books on Everything" thread.

Feel free to ask follow up questions!

@threadapalooza #TPLZ21

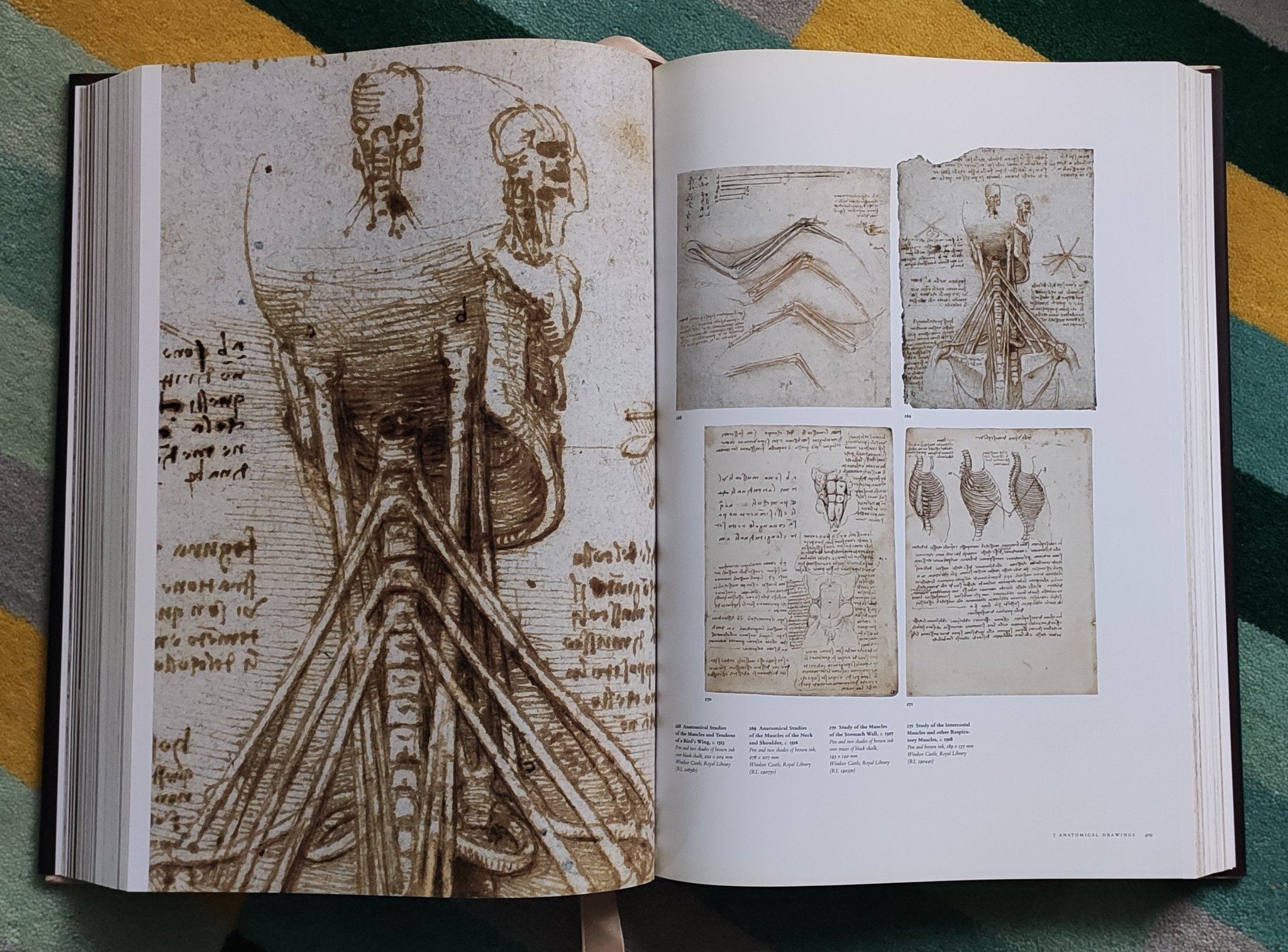

I get melancholy thinking about Leonardo, because he is hero worshiped too much for things he was not, and a biography is a good way to remind us of what he was, above all: an artist, and a man, and that should be good enough. Mortal, and fallible and striving with good cheer.

Intense, bustling, confident. For a man so supremely self-centred (properly understood) to be so sensitively self-aware is a shock. He is not the smartest of men, but it is the attitude with which he confronts life and the power of personality that sticks with you.

15 minutes every week on radio for 50 years, Alistair Cooke gave snippets from inside American life for the British listener. This is a selection showing America and America's understanding of itself over all those years, from the serious to the trivial.

How to speak persuasively? You would think this was as important now as ever, but we don't learn the tools of how to do it well. In fact the whole idea of studying rhetoric seems a bit dishonest, as Socrates insinuated 2500 years ago.

5) The Books of Babel: I've talked about this exceptional fantasy series before, shown is book 3 (I've got 1 & 2 on kindle). Hard to describe, but the best comparison in terms of feel and tone is Bioshock Infinite. Airship pirates! The final book (4) came out last month.

6) Long, slow, lavish historical novel, about the return of magic to early 19th century England.

That's all I need to say: if that description appeals to you, you will like it, if it doesn't, you won't!

That's all I need to say: if that description appeals to you, you will like it, if it doesn't, you won't!

7) This is a very important book to me, because it was the first discworld book I ever read when I was a teenager first really getting in to reading.

Also it is very good. The city watch has matured, Pratchett is comfortable in his world. Great characters and warmth.

Also it is very good. The city watch has matured, Pratchett is comfortable in his world. Great characters and warmth.

8) This is probably one of the most weird, slightly disturbing, and strange books ever written. It is also just gloriously inventive and well imagined. Think Dishonored meets supernatural horror.

9) Plato at his best has the freshness of a very smart person making stuff up as they go along, unemcumbered by the next 2500 years of history. This makes him entertainingly and rewardingly wrong. Which is the best way to be wrong.

10) Aristotle is clearer, less entertaining, but no less rewardingly wrong. A subtext in both this and Plato is the discussion what are and should people be like? And the conviction that this is the central question from which to consider political order.

11) Tocqueville's America is still the America of the Founding Fathers, before the industrial age and expansion into the West remade the USA.

I use the book as a place to think, a picture of people and of mores that provokes questions and consideration.

I use the book as a place to think, a picture of people and of mores that provokes questions and consideration.

12) On Liberty, Utilitarianism, Considerations on Representative Government, and The Subjection of Women.

We stray from Mill in different directions, but always come back, because his understanding turns out to be deeper and more subtle than we previously thought.

We stray from Mill in different directions, but always come back, because his understanding turns out to be deeper and more subtle than we previously thought.

13) More fiction:

A charming, melancholy, surreal and funny tale of a struggling writer and college english teacher having a mid-life crisis. It made me laugh out loud, which basically never happens.

A charming, melancholy, surreal and funny tale of a struggling writer and college english teacher having a mid-life crisis. It made me laugh out loud, which basically never happens.

14) A struggling American scholar in England raises her prodigy son alone. Well, alone apart from a Kurosawa film and *the entire world literary canon*.

A remarkable book composed of wry commentary on daily life, and unashamed intellectual referencing of almost everything.

A remarkable book composed of wry commentary on daily life, and unashamed intellectual referencing of almost everything.

15) Gorgeously written, smart, with great characters (particularly the flawed heroine), and with an ambience to die for. It explores the interplay of how expectations and understanding colour how we perceive the world and the consequences when people get caught in the middle.

16) How does it feels when life doesn't quite turn out how you hoped it would?

Another smart, wry mid-life crisis book about what it means to be, or not to be, an artist; what we need, and what we get, from our relationships with others.

Another smart, wry mid-life crisis book about what it means to be, or not to be, an artist; what we need, and what we get, from our relationships with others.

17) Heresy: arguments for the value of biodiversity always strike me as at heart a romantic horror at the loss of uniqueness.

Regardless, this is the classic book on what biodiversity is, how it came to be, and what is happening to it. Wilson is a fine writer.

Regardless, this is the classic book on what biodiversity is, how it came to be, and what is happening to it. Wilson is a fine writer.

18) The more I re-read this book, the more wrong I think it is: it unfruitfully conflates the regulatory feedback of a complex dynamic system with evolution. It is quite interesting and fun though, the biogeochemistry of Earth.

19) This is the Folio Society edition of Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man, which is basically a transcript of the beloved 1973 BBC series that I talk about ad nauseam. Watch the series instead of reading the book. [But I got it on sale for less than £10!]

20) A deep, broad book about how to usefully think about many things that David's worldview connects.

I agree with the parts I know most about, and disagree with the parts I know least about, which is surely a strong signal that it has much more to teach me on a re-read!

I agree with the parts I know most about, and disagree with the parts I know least about, which is surely a strong signal that it has much more to teach me on a re-read!

21) It took my a long time to warm to Dickens. The key is that I discovered he isn't who I had been led to believe; he is a much sharper and more conflicted thinker and more nuanced observer than the broad brush picaresque moraliser of popular imagination and TV adaptation.

22) I remember most the theme of disillusionment: that one has wasted your efforts on a subject or a person who never was and never could embody the purpose and greatness you were looking to for fulfillment. A novel of ideas cunningly disguised as 'A Study of Provincial Life'.

23) Multiple character studies centred around a Parisian boarding house, featuring such staples of 19th C. French literature as the upwardly mobile young man on the make, all twined together around an emerging moralistic melodrama.

24) Where to begin? Often abridged, which rather misses the point of a sprawling novel of digressions, backstory and colourful vignettes. It is the piling up of things that builds the stage needed for Jean Valjean, Javert, Fantine, Cosette, Marius to play out their epic drama.

25) Russians!

I don't really like short stories. But of all the short stories that I don't like, Chekhov's are by far the best.

The only memory that lingers is of a story that truly drove home the soul crushing misery of abject rural poverty. And I can't even find its name.

I don't really like short stories. But of all the short stories that I don't like, Chekhov's are by far the best.

The only memory that lingers is of a story that truly drove home the soul crushing misery of abject rural poverty. And I can't even find its name.

26) What makes a great man, for whom the laws of morality are suspended, and history bends to his will? Is Raskolnikov the Joker redeemed through God? Is twitter full of Raskolnikovs and Underground Men? I need a re-read.

27) I've read this twice, and I'll read it again and again, because there is no getting to the bottom of it. This is the opposite of Middlemarch, it isn't a novel of ideas, even though Tolstoy wants it to be, its a novel of beautiful moments and feeling.

28) The first time I read it I enjoyed the ideas. The second time I felt sorry for everyone involved; the way their principles push them one way or another; a look at the ways people can be led to their convictions, through temperament, tradition or philosophical ideals.

29) What happens when a system becomes too broken to fix itself? It is hard to know what to make of the French revolution because its long shadow as a model and a warning colours our understanding. Was it necessary? Inevitable? Did it have to end badly?

30) The "long 19th century" changed everything.

The industrial revolution marks a break with life for the mass of humanity not seen since settled agriculture and the rise of cities.

Part 1: The French Revolution, Napoleon, and the birth of new ideas in every sphere of life.

The industrial revolution marks a break with life for the mass of humanity not seen since settled agriculture and the rise of cities.

Part 1: The French Revolution, Napoleon, and the birth of new ideas in every sphere of life.

31) Part 2: Industry accelerates; railways and telegraphs and steam ships make the world smaller, and larger; nationalism reshapes the political map of Europe; cities boom (for good and ill); vast changes produce winners, and losers, and ideologies to justify and mobilise both.

32) Part 3: New expectations, new demands; politics, ideas and struggles before the coming of the Great War.

Hobsbawm was a Marxist, which means he took seriously the key question of the age: what does this economic and social change mean for us? How should we live with it?

Hobsbawm was a Marxist, which means he took seriously the key question of the age: what does this economic and social change mean for us? How should we live with it?

33) A reminder of the importance of what ideas are in the air.

What Russia began with, and perhaps needed, was a liberal bourgeois revolution. But revolutions eventually lead to rule by ruthless opportunists, who can tear down, and hold together.

What Russia began with, and perhaps needed, was a liberal bourgeois revolution. But revolutions eventually lead to rule by ruthless opportunists, who can tear down, and hold together.

34) I've read this book twice and I still couldn't tell you what happens. I know I didn't like it the first time, and did like it the second. Style over substance? Possibly.

The archetype of cyberpunk - hackers, losers, drugs, crime, urban sprawl, the mind and the machine.

The archetype of cyberpunk - hackers, losers, drugs, crime, urban sprawl, the mind and the machine.

35) Surviving alone at the end of the world with the vampire zombies. It's been so long since I read this that all I know is it doesn't play out the way you expect - that and a sense of constant questioning, we and the protagonist always learning more about the world.

36) The little remaining knowledge of the past world kept alive as a sacred duty by an order of monks in the desert. Time passes, society rebuilds, will history repeat itself?

A classic and definite inspiration for post-apocalyptic stories that comes after, think Fallout.

A classic and definite inspiration for post-apocalyptic stories that comes after, think Fallout.

37) Six pilgrims journey to the shrine of the Shrike on the planet Hyperion, each with their own reason, and their own tale, told on the journey.

The three sequels I can do without, but the original is a masterpiece, of atmosphere, love, loss, horror, intrigue.

The three sequels I can do without, but the original is a masterpiece, of atmosphere, love, loss, horror, intrigue.

38) Lost at sea and stranded on a remote island with a mad scientist and his creations. Who knew biopunk was invented by H.G. Wells in 1896?

An early entry into the genre of "Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

An early entry into the genre of "Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

39) This is a good entry point for ethics, because the subject lends itself immediately to thought experiments and reasoning on issues people deeply care about. The book is brief, clear, and well written; not deep, but a perfect introduction.

40) This is about the best mental workout you can get outside of mathematics.

When is a moral theory self-defeating? Rationality, time preference, personal identity, future generations and the repugnant conclusion.

A masterpiece, a foundation and challenge to moral reasoning.

When is a moral theory self-defeating? Rationality, time preference, personal identity, future generations and the repugnant conclusion.

A masterpiece, a foundation and challenge to moral reasoning.

41) Need to re-read this, but as I remember the basic premise is my favorite: what if the central problems of philosophy are not what you think, but artifacts of the way you are framing the questions?

42) My second favorite Dennett book: a scientifically informed take on Humean-flavoured compatibalism. My takeaway from both Dennett and Hayek is that freedom is an epistemological problem, not an ontological problem.

43) Sometimes you get more out of reading the secondary literature. I find The Prince glib, and the Discourses tedious, but a lot of interesting stuff has been written about the meaning of Machiavelli, and this is as good a place to start as any!

44) An underrated classic to actually read: once you get used to the roundabout poetical way they wrote in the 17th C. Hobbes is surprisingly insightful, humane and occasionally wry.

Parts I and II only, III and IV are mostly theological: excellent for context, not for interest.

Parts I and II only, III and IV are mostly theological: excellent for context, not for interest.

45) Another influential inventor of the modern way of justifying political authority. These classic text are always worth re-visiting because when we first read them with modern eyes our own lack of understanding tends to strip them of nuance. We look to refute, not to engage.

46) I hold that this long essay is the fountainhead for almost every influential mistake in understanding society in the subsequent 250 years.

But Rousseau is such a provocative and entertaining writer!

But Rousseau is such a provocative and entertaining writer!

47) Caveats: the first time I read this book I hated it; I am not a fan of Roger Scruton; this is not an easy read.

Yet, despite those things: to do justice to the range, depth and difficulty of Kant's thought in 100 pages is nothing short of miraculous.

Yet, despite those things: to do justice to the range, depth and difficulty of Kant's thought in 100 pages is nothing short of miraculous.

48) Peter Singer is an excellent writer. Hegel was a terrible writer. More than anyone else his works lead you to need someone else to do the heavy lifting of excavating what on earth is going on. Because there are interesting things there, enough to infuriate everyone.

49) This is a boring book. I agree with its critics, both libertarian and socialist. Yet despite those things it is a hugely impressive intellectual achievement. All academic political philosophy for the past 50 years starts here.

50) This is not a boring book.

It is a very misunderstood book, both on purpose and by accident. Unlike Rawls it is not comprehensive or systematic, but best thought of as an attempt to bring together a series of meditations around the concept "liberty upsets patterns".

It is a very misunderstood book, both on purpose and by accident. Unlike Rawls it is not comprehensive or systematic, but best thought of as an attempt to bring together a series of meditations around the concept "liberty upsets patterns".

51) I find it very hard to find good architecture books. They either have few words, and say very little; or many words, and say very little.

This book sets out to say very little, and succeeds admirably. It is basically "100 tweets about architecture" but in book form.

This book sets out to say very little, and succeeds admirably. It is basically "100 tweets about architecture" but in book form.

52) This textbook actually manages to say a great deal about the things architects find it difficult to convey. But it does it less in words, and more in exquisite pencil drawings. It isn't about meaning and context, it is about the principles and elements of design.

53) Another classic textbook at the other end of the scale: a bit dry, and vastly more wordy, a history of architecture with a focus on context and meaning.

54) I first saw this book in an art gallery, where it was on a sofa in the middle of an exhibit for people to stop, rest and browse. I so loved the artwork that I bought it! The text is not so great, but it is a wonderful visual record of the history of imagined futures.

55) When urbanism and economics collide. Bertaud, a storied urban planner, tries to explain to his collegues the use and ignorance of economic principles with the zeal of a convert. Cities as labour markets, transport, housing, policy. Detailed but largely non-technical.

56) Neal Stephenson time. One of my favourite authors for the scope, imagination and deeply researched nature of his books, marrying together adventure and ideas.

Here a near-future society of cultural tribes (confucian, neo-victorian etc.) meets My Fair Lady via educational AI.

Here a near-future society of cultural tribes (confucian, neo-victorian etc.) meets My Fair Lady via educational AI.

57) Computer science and mathematics, modern startups and WWII code breaking. The nerd culture masterpeice, back when that meant geeking out about science and technology, not media franchises and memes.

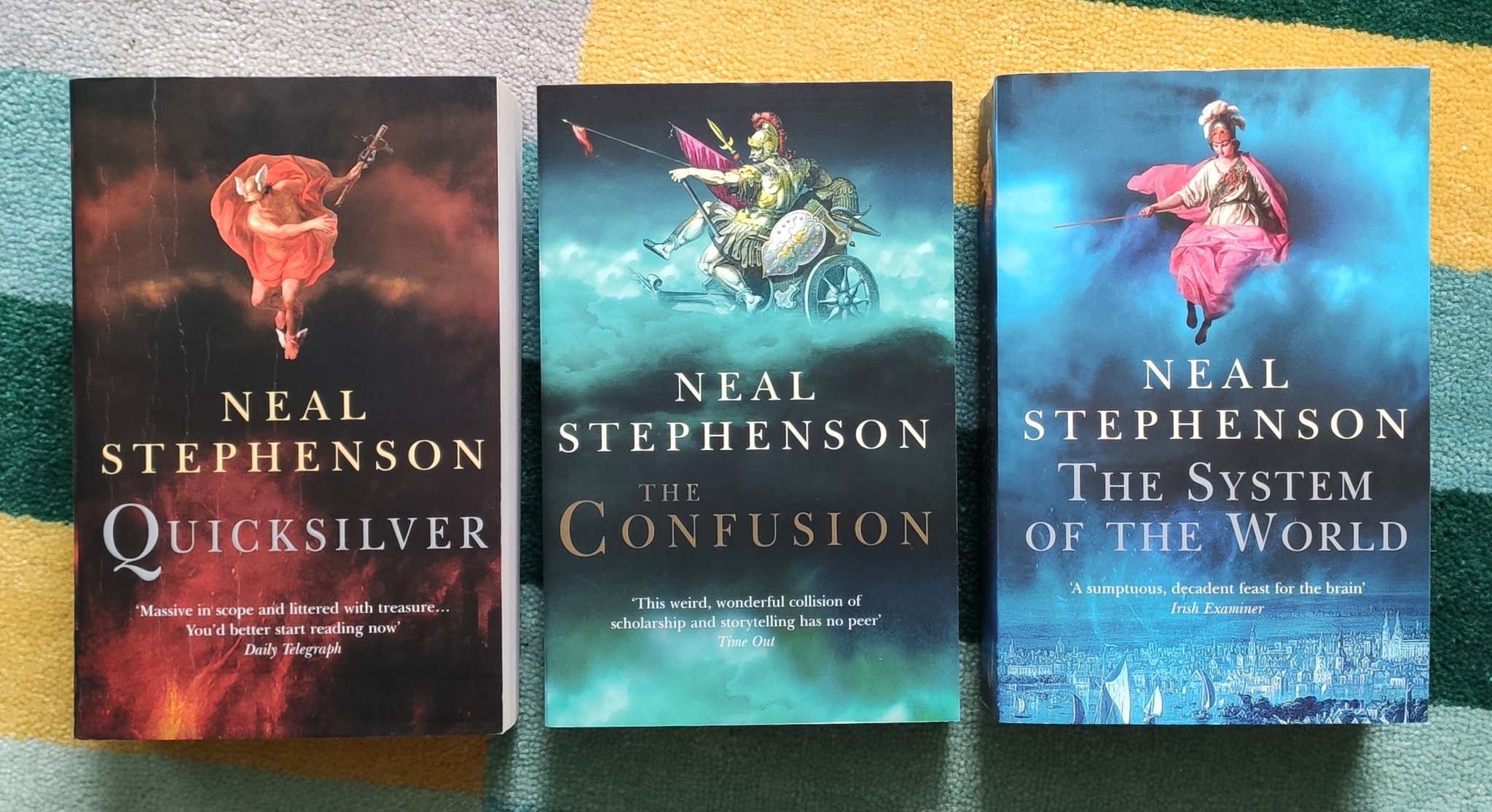

58) I'm counting The Baroque Cycle as one work.

Vagabonds, soldiers, whores, slaves, traders, scholars, Newton, Leibniz, Louis XIV, the Duke of Marlborough. Colonial America, Mexico, India, The Royal Society. Everything is here in an historical adventure epic.

Vagabonds, soldiers, whores, slaves, traders, scholars, Newton, Leibniz, Louis XIV, the Duke of Marlborough. Colonial America, Mexico, India, The Royal Society. Everything is here in an historical adventure epic.

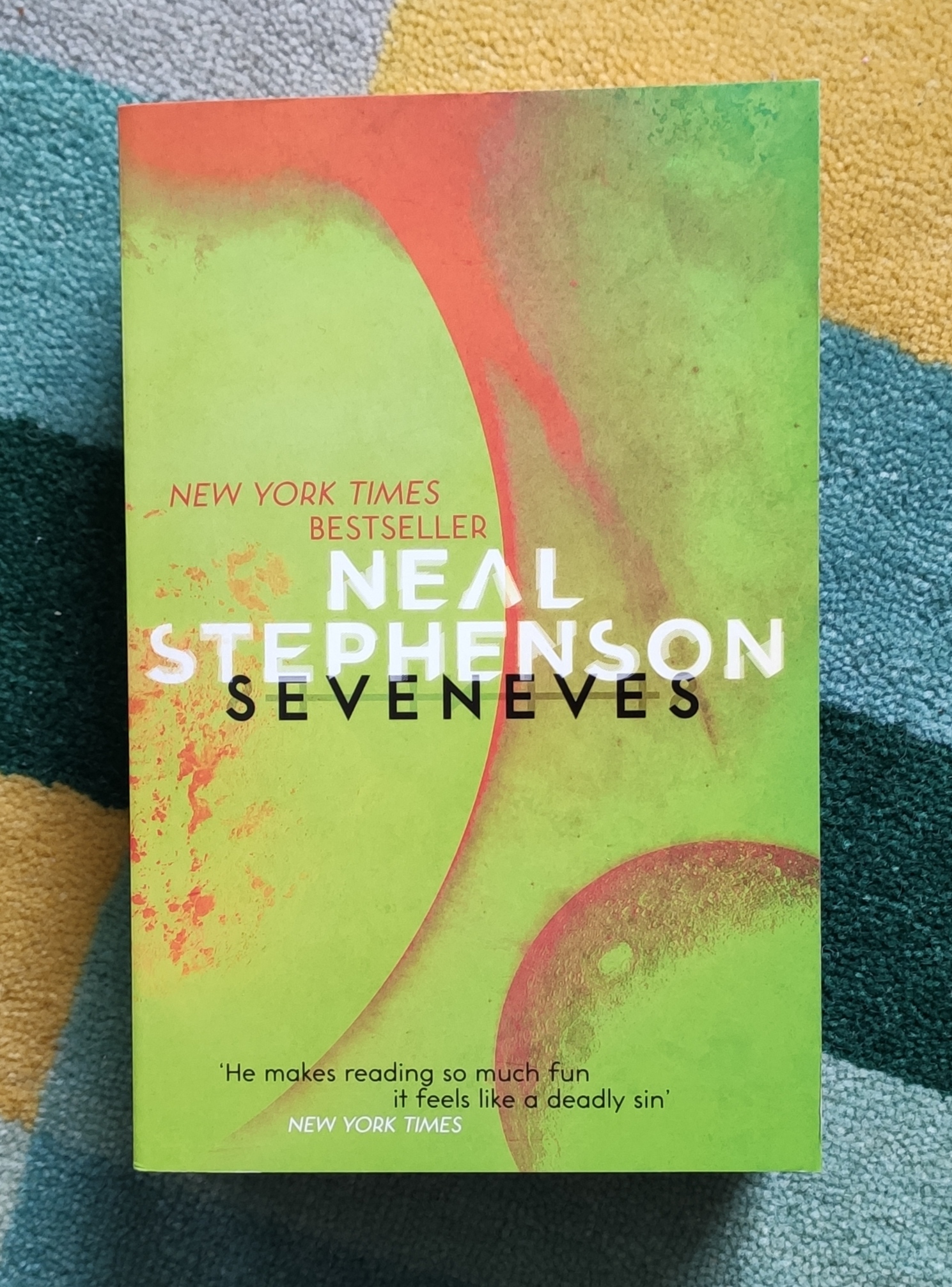

59) Starts as a hard sci-fi telling of how we react and adapt to the end of the world. A celebration of science and engineering and determination. Becomes a speculative tale of the far future of humanity in this new reality. I enjoyed both parts, some only liked one or the other.

60) War, it has a bad reputation, but what does it really mean, and how has it changed over time? Can war be constructive, not just destructive? You get more interest if you're seen taking a contrarian stand, but the answer in the end is: it depends.

61) All of Rome in 300 pages? Well yes, and no. More Rome: An Overview with discursive Further Reading suggestions. In fact Chapter 1 is titled "The Whole Story" (12 pages). A little dry and academic, but there should be more books like this for All The Things.

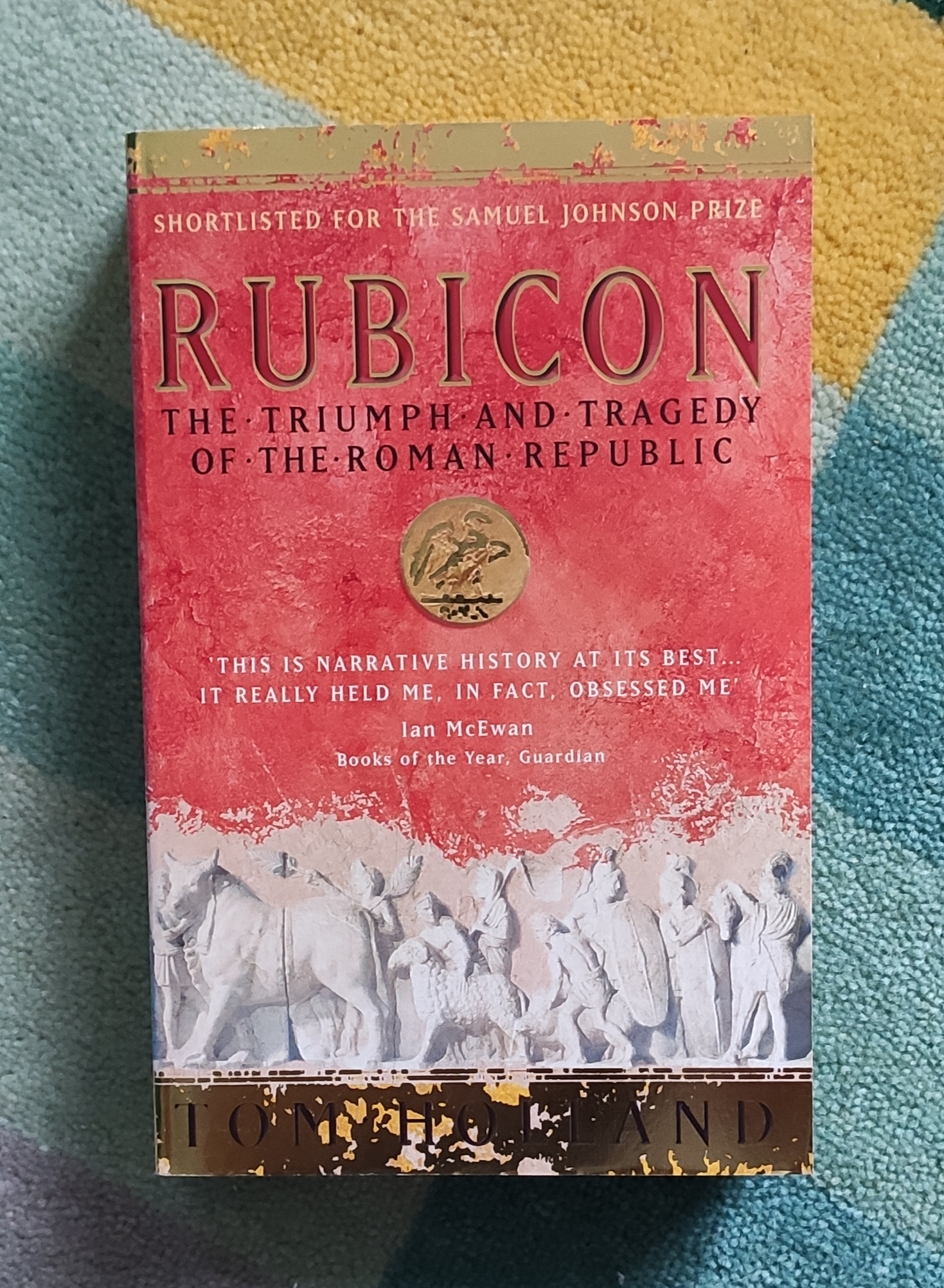

62) More focussed and more accessible, Holland is a good writer of popular history. This and Persian Fire (also good) made his name. The story of the last years of the Roman Republic. The age of Caesar, Pompey, Cato, Cicero.

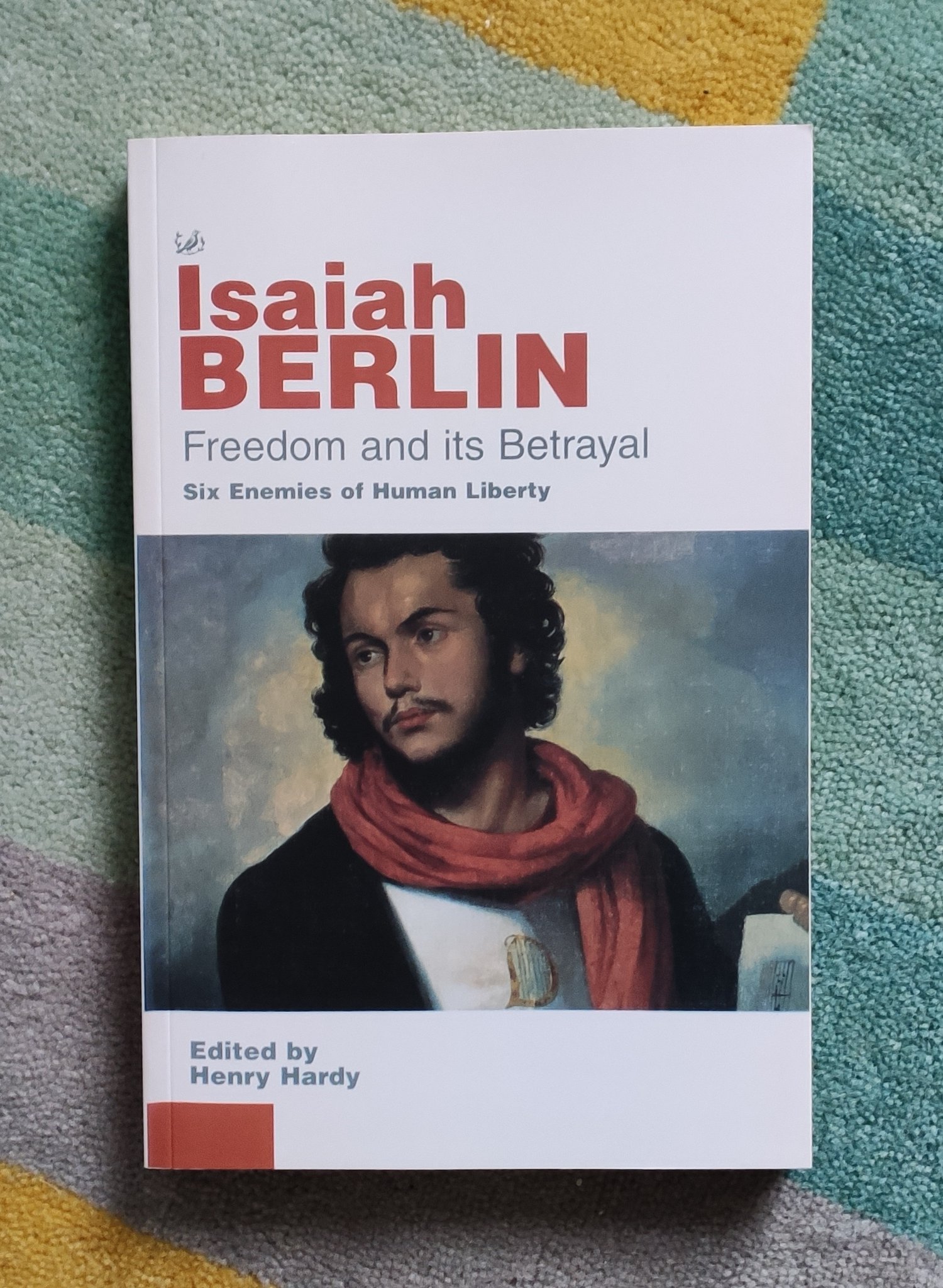

63) How to understand freedom is one of the most frought topics in all of politics. Berlin is nuanced and learned, and he introduced the terms positive and negative liberty; that have been misunderstood, re-labelled and re-used by legions of less interesting thinkers ever since.

64) Berlin was above all an historian of ideas. These six essays (transcripts of radio broadcasts) are each about understanding a thinker (Helvetius, Rousseau, Fichte, Hegel, Saint-Simon, Maistre) whose ideas (often about freedom itself) Berlin considers antithetical to freedom.

65) Another famous book that nobody reads and even fewer understand. It is not a cricism of the welfare state, it is a criticism of central planning, and the dangers of setting up authorities with the power to decide the value of all things, to moralise the economy.

66) Greatly expands upon The Road to Serfdom, not a warning, but a detailed explanation of the power and principles of a free society. Part 3: "Freedom in the Welfare State" is once again not an attack, but an exploration of what is and is not consistent with those principles.

67) We all need identity. To know who we are, to belong to various groups. We are individuals, we are groupish. We all need dignity, for our identities to be recognised and respected, and if we feel we are not getting it we will fight for it. Yet an oddly intellectual book.

68) The sequels are very good despite their pacing issues. But this is a masterpiece. Historical fiction at its finest. I've tweeted it before but it is worth repeating: I think Mantel's Cromwell is the best characterisation in the history of literature.

69) Father-son road trip and exploration of mental health and scholarship, dressed up with wry motorcycle related wisdom and serious if idiosyncratic interpretation of ancient greek philosophy. Once a dangerously trendy book, definitely original.

70) The book is better than the film.

How much should we feel guilty for things people (including ourselves) believe we ought to be responsible for but can't control?

The crux is you either connect with the narrator, and love the book, or don't and despise it.

How much should we feel guilty for things people (including ourselves) believe we ought to be responsible for but can't control?

The crux is you either connect with the narrator, and love the book, or don't and despise it.

71) The film is better than the book.

The work that spawned many imitators and video games. The book gives more space for the characters to breathe and interact in their strange new reality. The writing is a bit basic. The theme is more Lord of the Flies than The Hunger Games.

The work that spawned many imitators and video games. The book gives more space for the characters to breathe and interact in their strange new reality. The writing is a bit basic. The theme is more Lord of the Flies than The Hunger Games.

72) I found this 1988 book in the college library, and later bought myself a used copy. I can't remember if it is good! But the concept of education cross-cuts more or less *everything* because at root it is about how we become who we are. Potentially a most powerful tool.

73) Another weird old book, a 1983 textbook of classic sociological theory. Looks at the origin of sociological thinking as a response to the rise of urban industrial capitalism. Always good to get inside how a field thinks. Clear, direct, no soft-pedaling or verbosity.

74) What about pre-industrial sociology? We call that Anthropology! This is a lovely little book centred on and enlivened by the authors' own fieldwork. A field above all about what things signify/mean to people, in the context of their lives.

75) A whole book about what a concept means/signifies! Books like this are an exploration, not an analysis. It isn't about coming to an answer, but gaining an understanding. The subtitle hits the key points, longing, and visual. Images, in the sense of pictures, and impressions.

76) In the old days national newspapers ran good promotions for students, buy a Guardian for (the student price of) 20p, go to the JCR and pick a free book.

I knew only it was about WWI, nothing else, not even that it was a translation and so from the German POV. It was good.

I knew only it was about WWI, nothing else, not even that it was a translation and so from the German POV. It was good.

77) One day in the Gulag.

Solzhenitsyn is more known for The Gulag Archipelago, a long boring history detailing the machinery of atrocity. But what does it actually feel like to be in a forced labour camp? You only need one short book to get a good idea.

Solzhenitsyn is more known for The Gulag Archipelago, a long boring history detailing the machinery of atrocity. But what does it actually feel like to be in a forced labour camp? You only need one short book to get a good idea.

78) This is a book about America in Vietnam. What is astonishing is that it was written in 1955! We never normally learn about life in the dying embers of French colonialism. Here we do, in Greene's lush, worldly novel. Also a 2002 film with a wonderfully languid Michael Caine.

79) There is a tension between our needs and expectations and what society can provide. This book is part a warning that this can be fixed by changing us as much as by changing society.

But also to be careful wishing away friction and anxiety, you don't know what you might lose.

But also to be careful wishing away friction and anxiety, you don't know what you might lose.

80) Here are four large books that between them tell the story of Britain from 1956-1979; I think of them as the history of my parent's youth. It is mostly politics, pop culture, and the way we lived. Nothing compares when it comes to learning what Britain is really like.

81) It is a strange phenomenon how nations go through ages of optimism and ages of pessimism. The 60's was an age of optimism, a conservative country conquered by its own pop culture; an energy that masks the less obvious but ever present incompetence and strife.

82) Then in the 70's the energy passes and only the incompetence and strife remain. Yet objectively things are still getting better. The books are wonderfully even handed. Sandbrook doesn't understand economics, but that doesn't matter, neither did the people he is writing about.

83) I am reluctant to have opinions about other nations domestic politics because I realise how important all the details are to really understand the nuances of your own. For most people 3000 pages on this topic is too much, but it is a glorious rabbit hole for the curious.

84) What The Dispossessed is to Anarchism (an ambigious utopia) this book should be to Traditionalists. An upper-middle-class, civic minded, bourgeois family business in Hanseatic Lubeck. With all the appeal and tragedy, belonging and constraint that comes with dynasty.

85) I can't remember anything about this book, other than that I liked it! I've got a vague impression of Camus existentialism, Kafka surrealism, and Dostoyevsky alienation, all stirred together. But I don't know if that is accurate.

86) Doris Lessing wrote Shikasta, the book I hate the most ever. This however is extraordinary. A fractured narrative of depression, adultery, and communism. Most shocking is what (sex) life was like for women in the 1950's. Difficult, claustrophobic, eye opening, and draining.

87) I did not have to read this at school. But you can see why people do, a short simple book but with thematic depth, that should offer something to everyone. The book is better than the film, because it leaves more of the interpretation to you; but the film has Gregory Peck. 😍

88) 'X is not about X'

Is this thread really about books? No, its about me signalling my quality as a potential ally.

These ideas were so familiar to me that I was initially unimpressed. But I kept asking myself "what does a good job explaining it all in one place?" this book.

Is this thread really about books? No, its about me signalling my quality as a potential ally.

These ideas were so familiar to me that I was initially unimpressed. But I kept asking myself "what does a good job explaining it all in one place?" this book.

89) We don't talk enough about the law. Legal systems seems a closed world we have left to specialists. I always get the impression that sharp questions need to be asked, but I don't know enough to even begin. This book counts as step one. I've never yet found step two.

90) This is a book published in the wake of the first wave of anti-globalization protests, and enjoys arguing that more or less everything it believed was wrong. Feels a little nostalgic.

If you want to make things better your critiques must come from a place of understanding.

If you want to make things better your critiques must come from a place of understanding.

91) The personal view from inside China's industrial revolution. A nation speedrunning 19th Century Britain. It is not pretty: a society turned upside down, a people on the make. A brilliant, brutal and important book, full of vitality and desperation.

92) In a world of catastrophic sea level rises and genetically engineered food blights, an American businessman arrives in the Thai Kingdom illicitly searching for genetic diversity and entangles himself in the factions of domestic politics and the lives of migrants and refugees.

93) Lets talk The Culture. The Culture is the post-scarcity human future we should all hope we are lucky enough to get. Society is run by AI called "Minds" that treat pseudo-humanity like a charming hobby, which is pretty much how Culture citizens treat life.

94) The Minds and the citizens have however inherited our ethical idea of liberal interventionism, and like to involve themselves with helping other civilizations for their own good. Like an anti-prime-directive. As such the Culture utopia is often only the frame story.

95) Shown here are the first 3 books, all completely different in style and tone, all stand-alone. Phlebas is framed as a classic Sci-Fi action-adventure; Player a thoughtful meditation on games and society; Weapons a non-chronological character study of war and atrocity.

96) This is basically Thinking Fast and Slow but for sports performance, and from 1975! To perform at a high level you have to not consciously think about what you are doing, because conscious thinking is too slow. Train yourself to do the thing, then get out of your own head!

97) Trying to lift the lid on the mystery that was 20th C. classical music. The associated website contains listening samples for each of the chapters. I can't say it converted me, but it got me listening to people like Lou Harrison and Steve Reich.

98) Plays are still a bit foreign to me, I did not grow up going to the theatre. But Tom Stoppard's combination of sly slightly surreal humour and unapologetic intellectual meandering seems tailor made. This play is glorious.

99) Neither am I big on poetry, yet the first poem of this collection, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, is easily my favourite.

"Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?"

"Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?"

100) I started with Leonardo's life, I end with Leonardo's work. This humongous book is the pride and joy of my library, it was (long ago) a 21st birthday gift.

And there you have 100 Books @threadapalooza, I hope you all enjoyed it!

And there you have 100 Books @threadapalooza, I hope you all enjoyed it!