Thread

So prohibitive was its membership fee, so severely inflexible and exacting the terms of membership, that through the span of its existence, it had just 649 members.

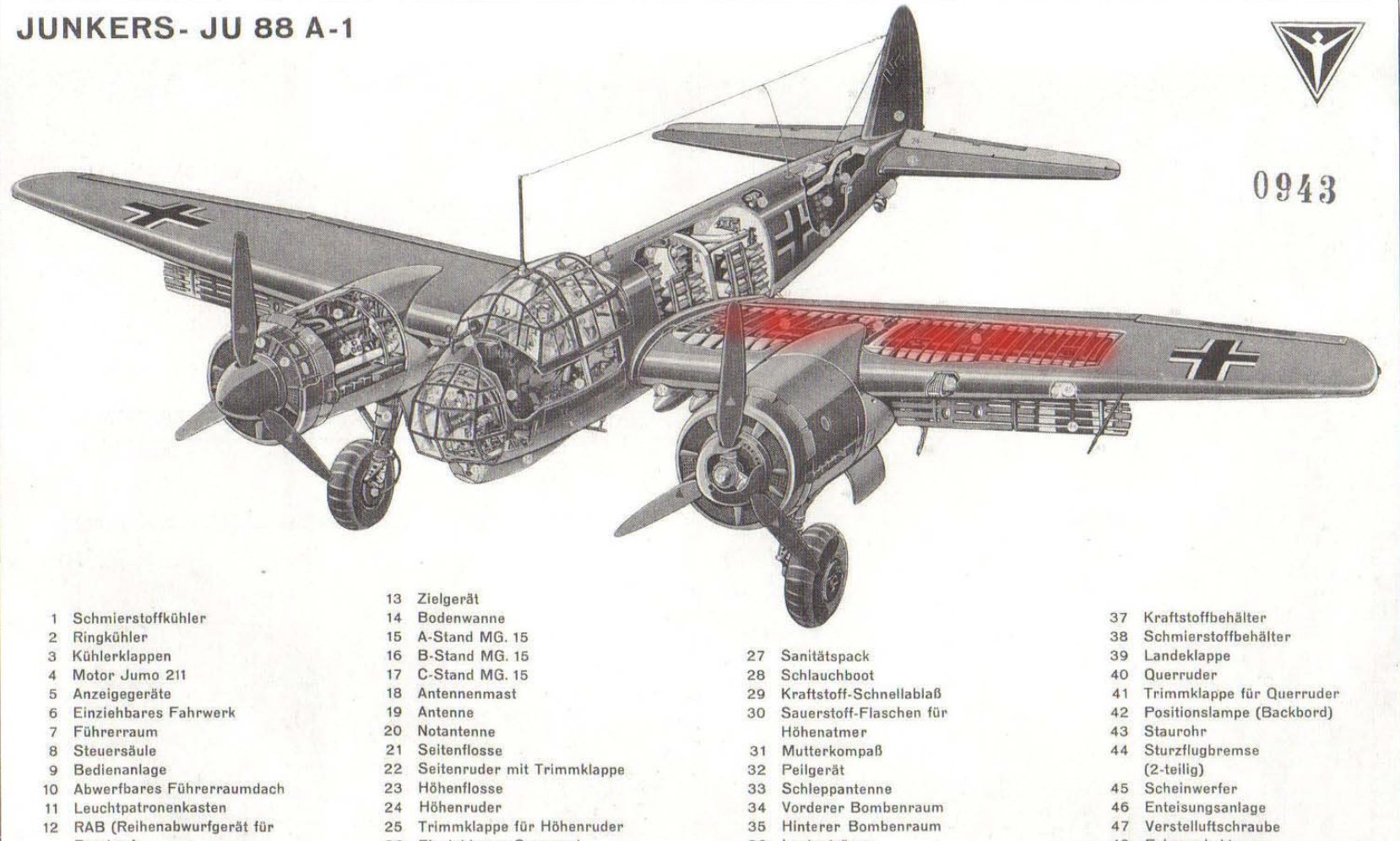

The story, curiously, has its beginnings in the locus of the fuel tank in the Spitfire and the Hurricane, the single-seat fighter airplanes used by Britain in the second world war.

That changed with the Spitfire. Those glorious elliptical wings with the mounted guns were considered ill-suited for carrying fuel, so they placed the fuel tanks directly in front of the cockpit, behind the Rolls Royce Merlin engine.

In the French skies, for the defence of France in 1940, those spanking new squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes got proper action for the first time.

That meant vertiginous high-speed dogfights with the German Messerschmitts. And incendiary ammunition coming at them at all sorts of angles.

The RAF fighters soon realised the grave folly of placing large fuel reserves right in front of the cockpit. It was an unwittingly easy target for the powerful 20mm Motorkanone guns on the German fighters.

The French skies were soon bespeckled with German and British fighters crashing and burning. By the summer of 1940, the Germans had complete control of mainland Europe and England was next on the list.

The Battle of Britain, aka the Air Battle for England that followed, was fought in the air by very young, hastily recruited airmen.

The average RAF fighter pilot was a little over twenty years old and unmarried. He hadn’t quite finished his formal education and had been recruited by the RAF less than ten months back. He had had roughly twenty hours of experience flying the Hurricane / Spitfire.

These unbelievably raw striplings were commemorated by the British nation as ‘The Few’. The phrase came from a wartime speech about the RAF made by Winston Churchill in August 1940. “Never in the history of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Anyway, we should come back to the fuel tank in the Spitfire. When the tank was hit, the ignited fuel almost instantly found its way into the cockpit.

At 20,000 feet in the air with a throbbing, screeching, mortally wounded engine and a plane that was diving upside down uncontrollably, brain numbed by acute panic, for the first few seconds, the pilot would lack any animate awareness of being on fire.

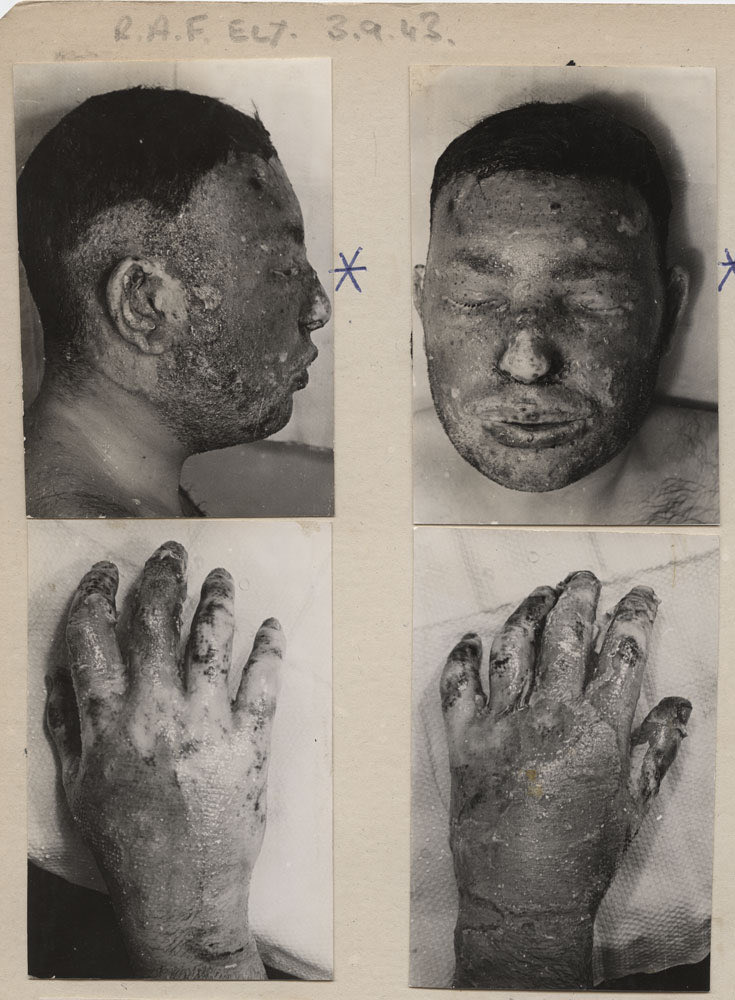

The inferno would be perceived only when the flesh on the hands could be seen hanging off like shreds of tissue paper.

With the will to survive stuck somewhere between the tongue and the gullet, the pilot’s primary instinct would be to take off the oxygen mask, pull off the goggles and slide the glass hatch back to bail out. That’s when the spout of flame would suddenly find more oxygen.

And the flames would gust upon the face and neck. It was like being in front of the nozzle of a flamethrower.

The first thing survivors would remember would be the unrelieved smell of grilled pork stuck in their nostrils.

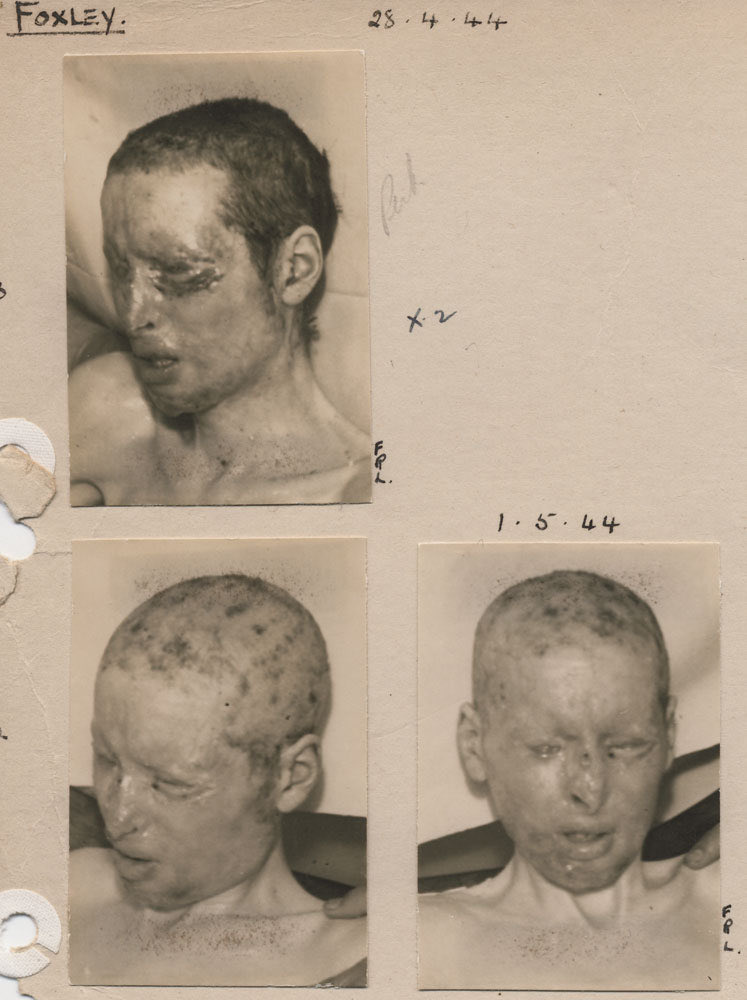

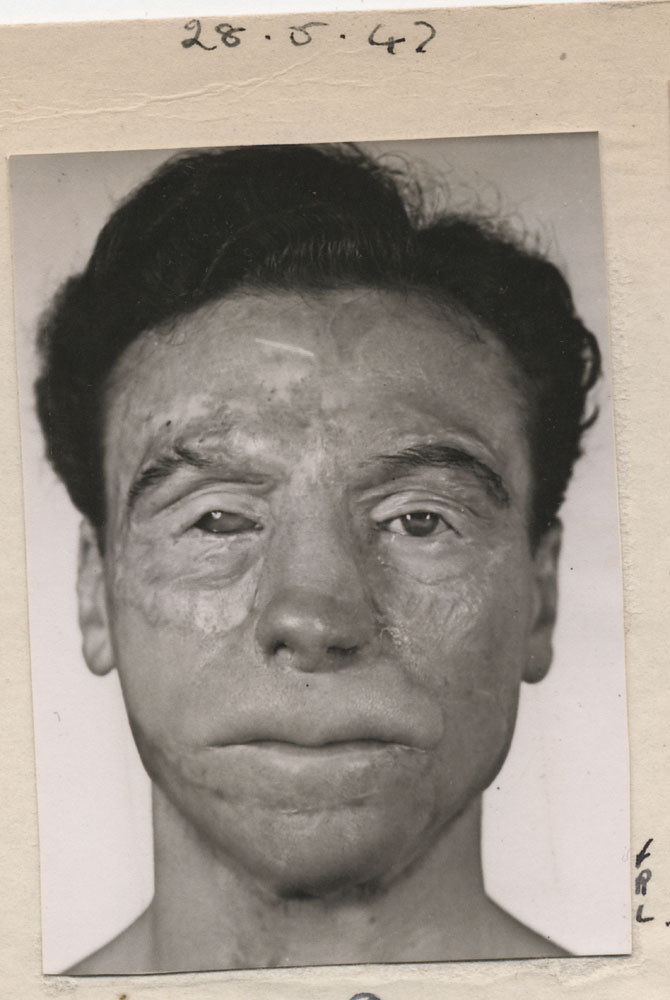

Surviving pilots from almost all the Spitfires and Hurricanes that crashed in the Battle of Britain had burns of the exact same description. The injuries were of such unvarying characteristics that they were admitted to the nomenclature of descriptors as ‘Airman’s Burns’.

The areas affected were described in an RAF Medical Services memorandum as: ‘Both wrists and hands, particularly the backs, the fingers, often the entire surface of the hands.’

'The face in the “helmet area”. When goggles are pushed back, the forehead, eyebrows and eyelids may be severely burned. The neck between the chin and collar, extending on both sides to the mastoid area behind the ears. The anterior and inner surface of the thighs etc.'

These were deep burns that seared the full thickness of the skin in areas of tremendous functional value, most vitally, areas that gave the face its outward form.

In 1938, there were only four full-time plastic surgeons operating in Britain. Harold Gillies, the most senior of the lot, had gained considerable prestige for his pioneering work on facial repairs.

The other three were Gillies’ protégés, inducted and mentored in their craft by the man himself. As part of the preparations for war, each one of them was assigned a hospital to take care of designated medical casualties.

Perhaps the most gifted of the three, Archibald McIndoe, was given charge of a cottage hospital in East Grinstead. This had been earmarked for RAF casualties.

Ward III in the cottage hospital was created and marked exclusively for the treatment of burns. It was where those piteous souls from the Spitfire crashes were conveyed.

Historically (before 1939), patients hardly ever survived severe burn injuries. The standard of care that prevailed had been developed for minor rather than major burns.

There was very little in his grounding or in available medical literature to show McIndoe the way. There was no wisdom of the elders. No-one had quite encountered such atypical burns, in these numbers, in patients who continued to live through their ordeal.

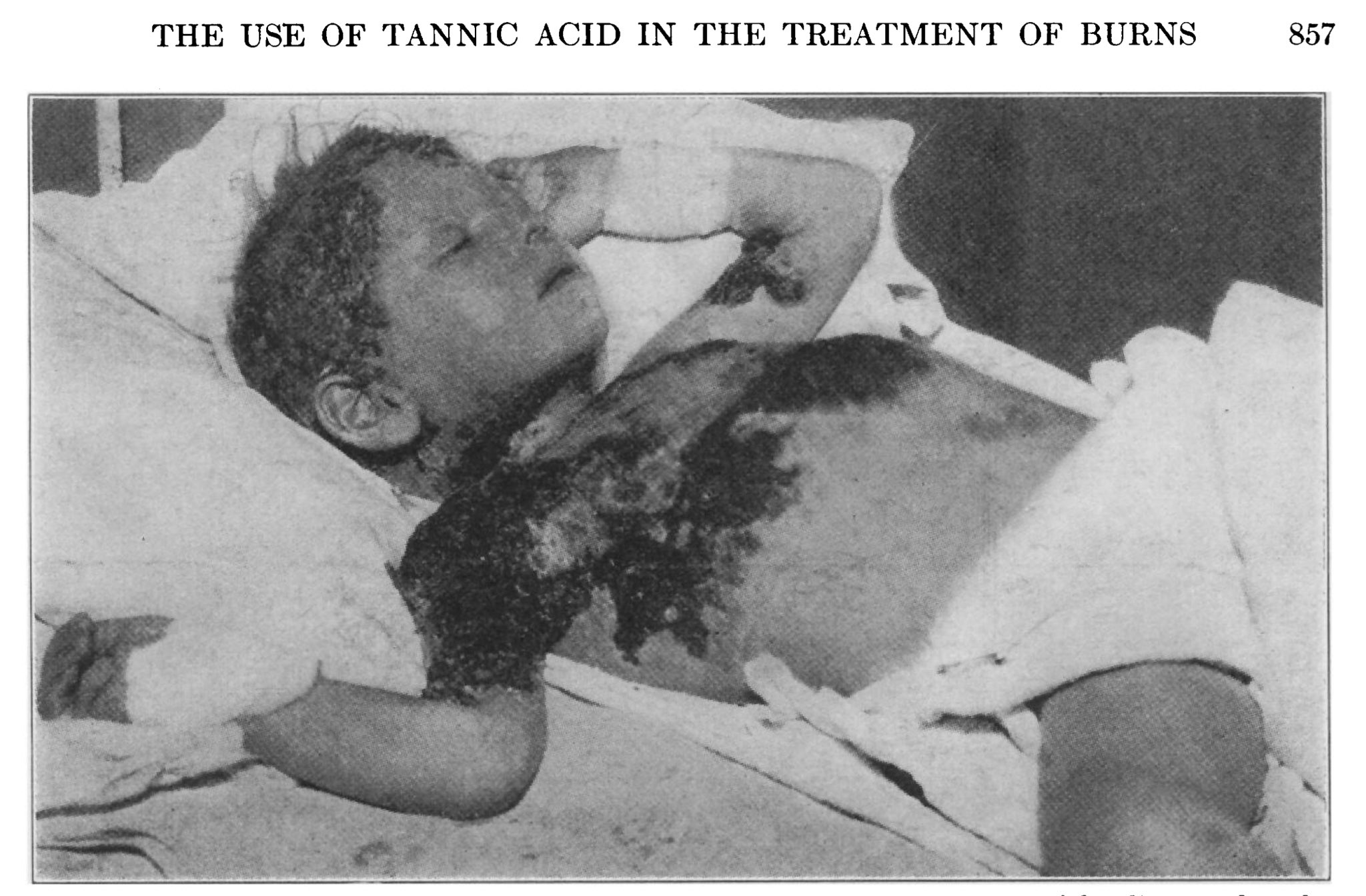

The only available treatment at that point was the application of tannic acid on the burnt skin. Tannic acid was used in the leather industry to stiffen and tan hides. That was precisely what it was meant to do on burnt skin as well: form a hard crust.

The treatment for burns with tannic acid was based on the theory that toxic material was produced at the site of the burn. Its absorption led to profound physiologic changes.

Tannic acid (it was claimed) precipitated the supposed poisonous material in the burnt area into a crust, thereby preventing its absorption.

It was a mistaken belief. The dark hard membrane didn’t allow the inflammatory exudate from the burnt surface to escape, letting it fester underneath. Sepsis would set in much sooner.

On the hands, particularly, the tannic membrane would constrict the circulation and cause gangrene and the loss of fingers.

McIndoe observed quite early on that the burns of pilots who landed in the sea fared much better than those who had parachuted down on dry land. As soon as he took over, tanning was stopped forthwith in ward III of the East Grinstead hospital.

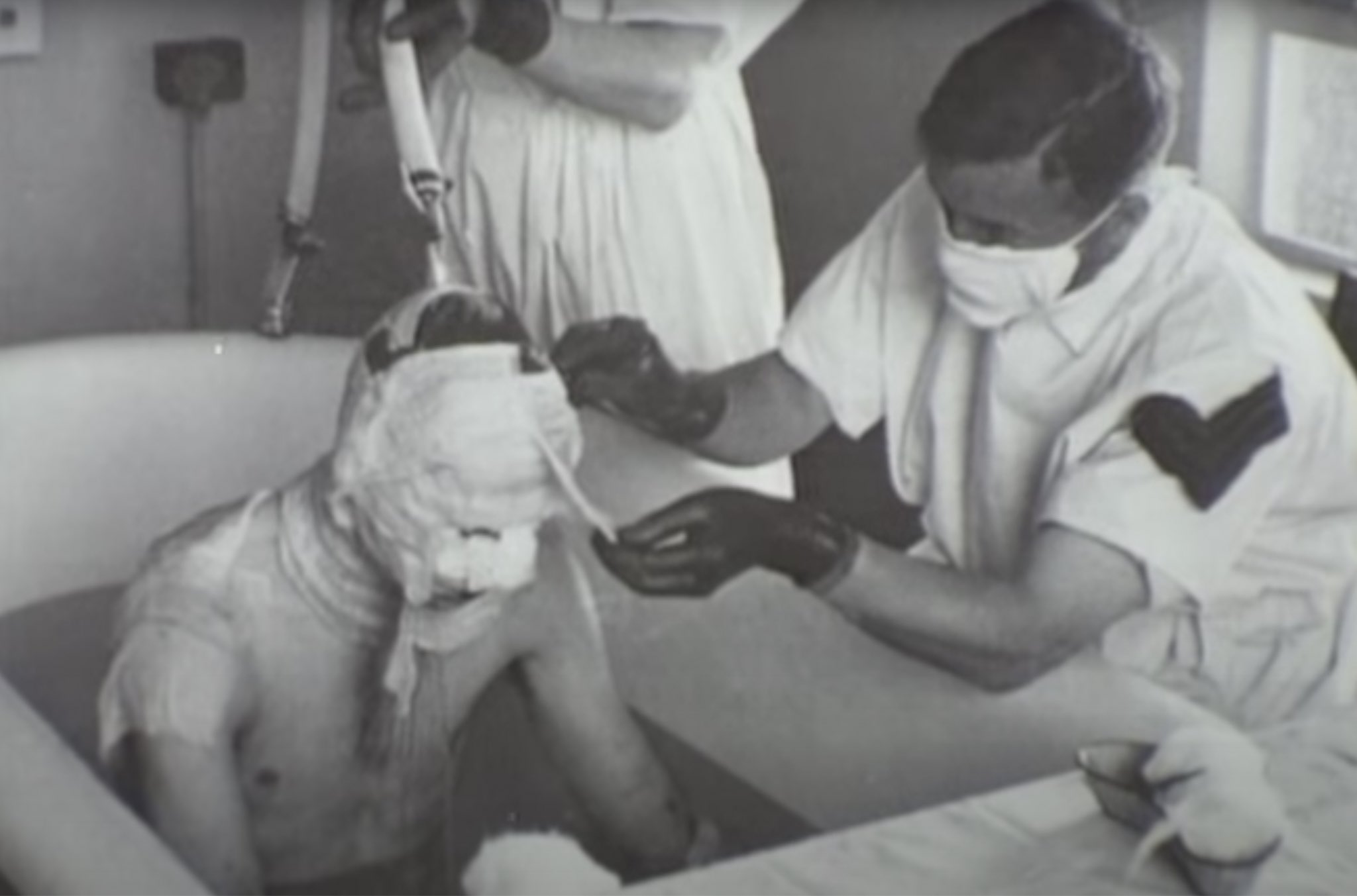

For all those severely burnt men under his care, he developed a simple salt bath treatment. And dressings of loose weave soaked in soft paraffin and oil.

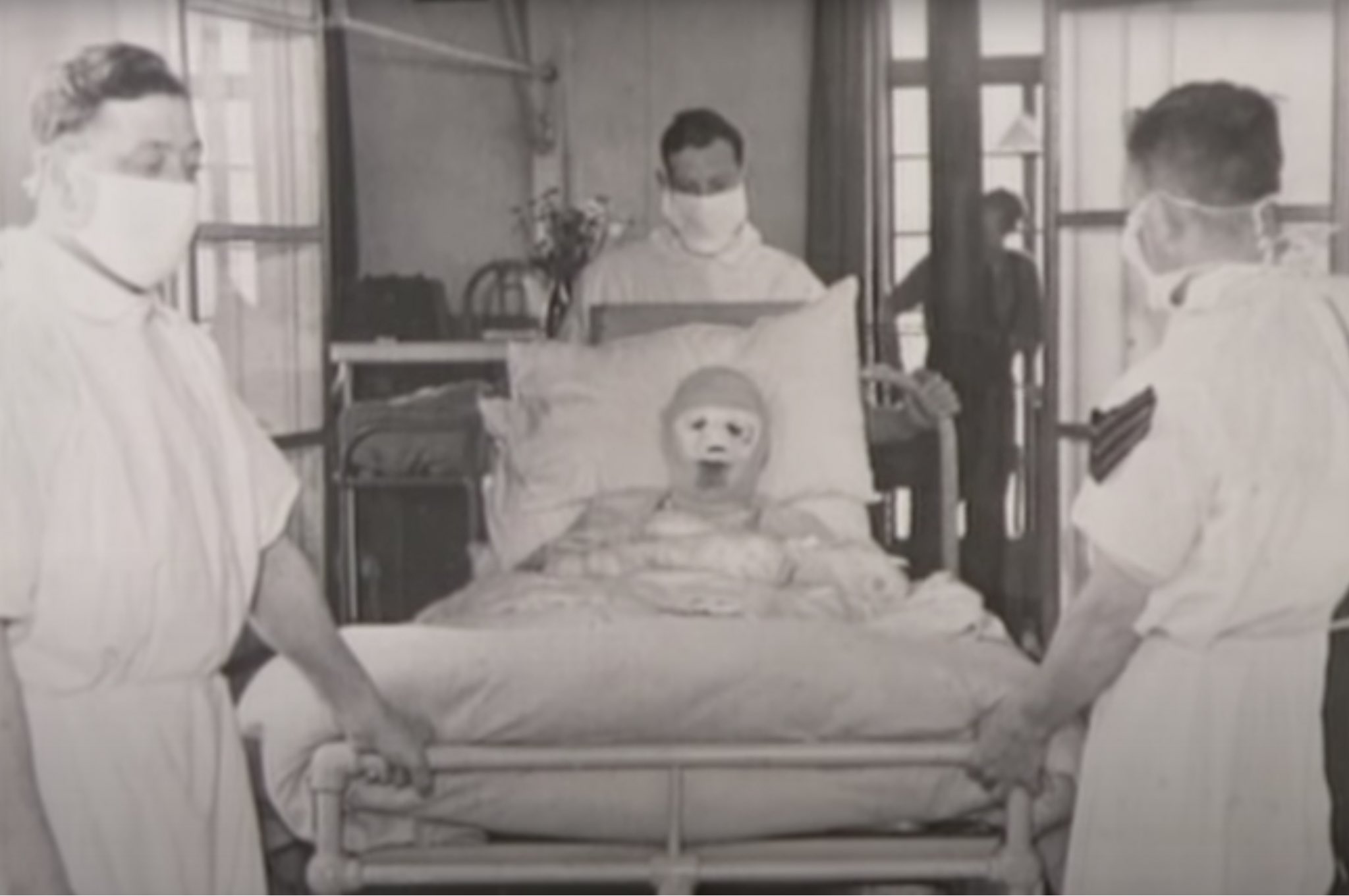

The beds and the bathing tubs were fitted with wheels so that they could be moved around. Beds also had removable headrests to allow facial dressings to be changed from all angles.

For the months that followed, Ward III was to become home to these badly burnt young airmen, these curiosities of aerial warfare. These were injuries they weren’t expected to survive till about a decade back, but now most of them would.

Each one of them barely in their twenties, rakish and stout-hearted and fearless, not finding it hard to charm the girls. Swaggering in the conviction that life was a romantic matter, he had “mocked grief and held disaster cheap”.

And then suddenly, in a flash, he’d find himself saturated in dread, looking like a pathetic monster. His face vaporised mercilessly by burning aviation fuel; his appearance frightening the life out of people.

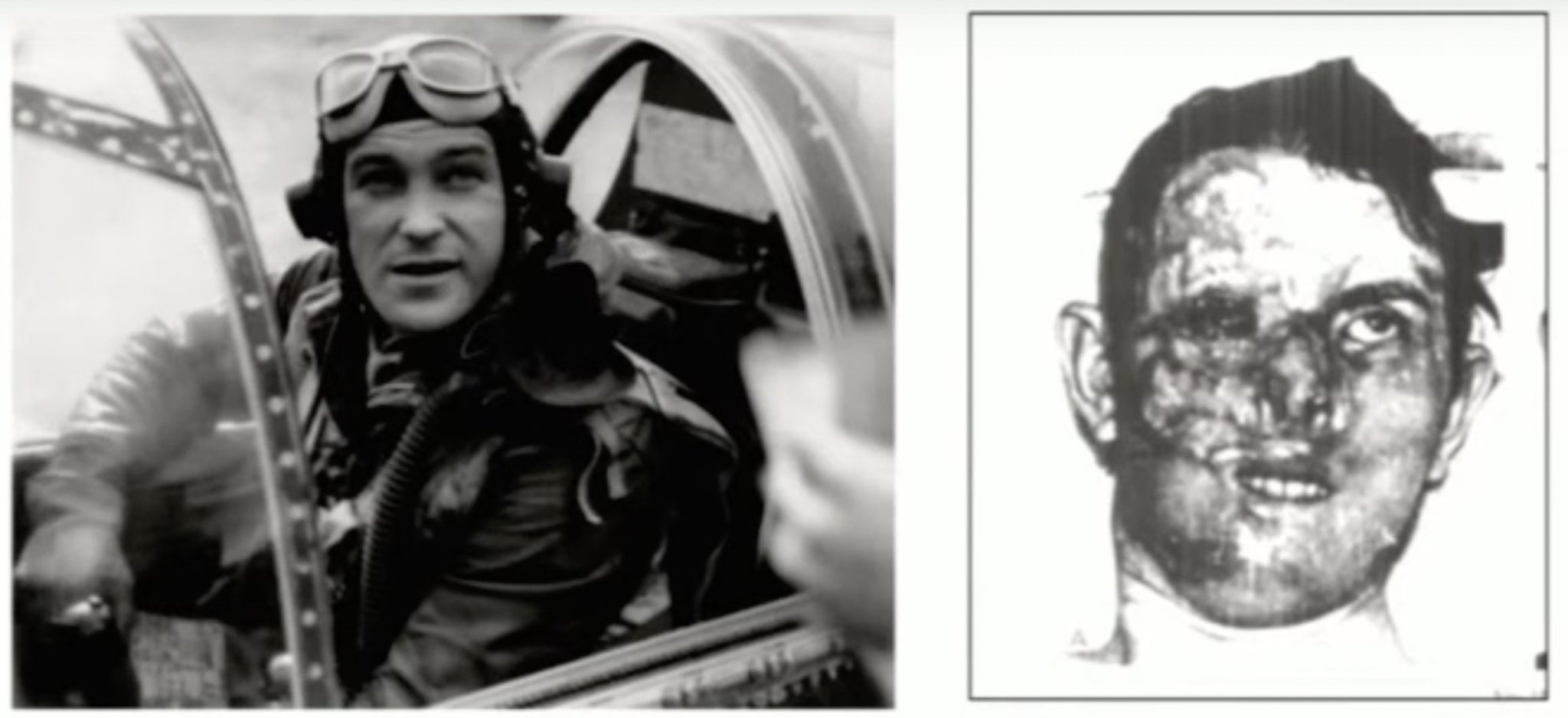

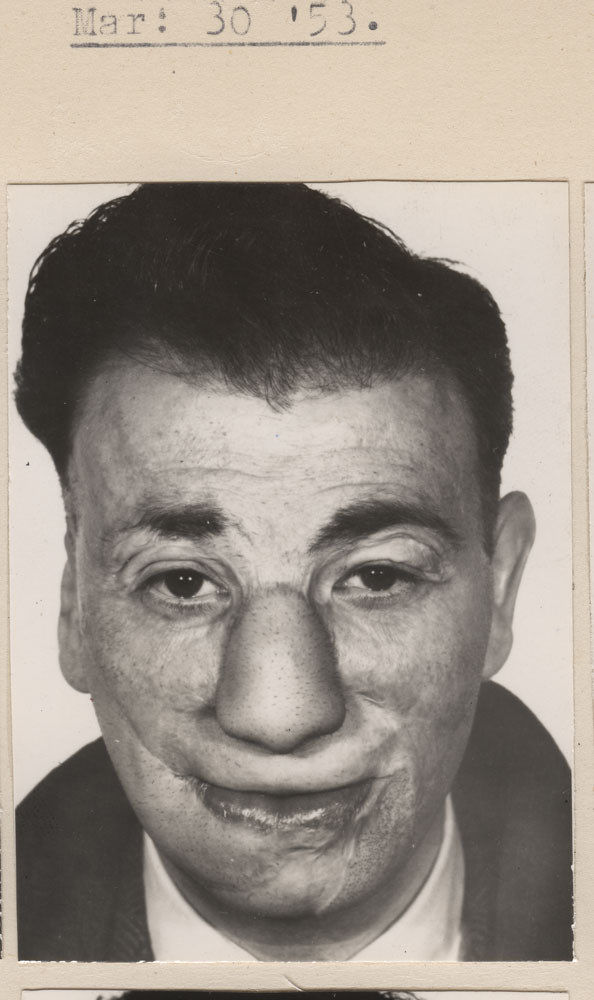

In his memoir Shot Down In Flames, Wing Commander Geoffrey Page (Pilot Officer then) wrote about his first glimpse of his damaged face. It happened in the operating room when the anaesthetist tied a rubber cord around his arm and searched the elbow pit for a suitable vein.

“I looked away and upwards, catching sight of myself in the reflector mirrors of the overhanging light. My last conscious memory was of seeing the hideous mass of swollen, burnt flesh that had once been a face.”

“The Battle of Britain had ended for me,” he wrote, “but another long battle was beginning.”

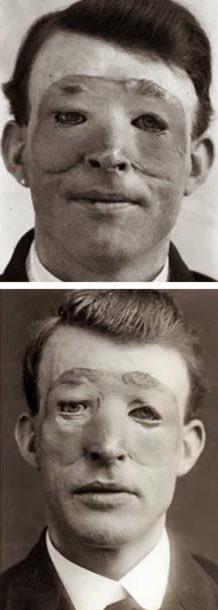

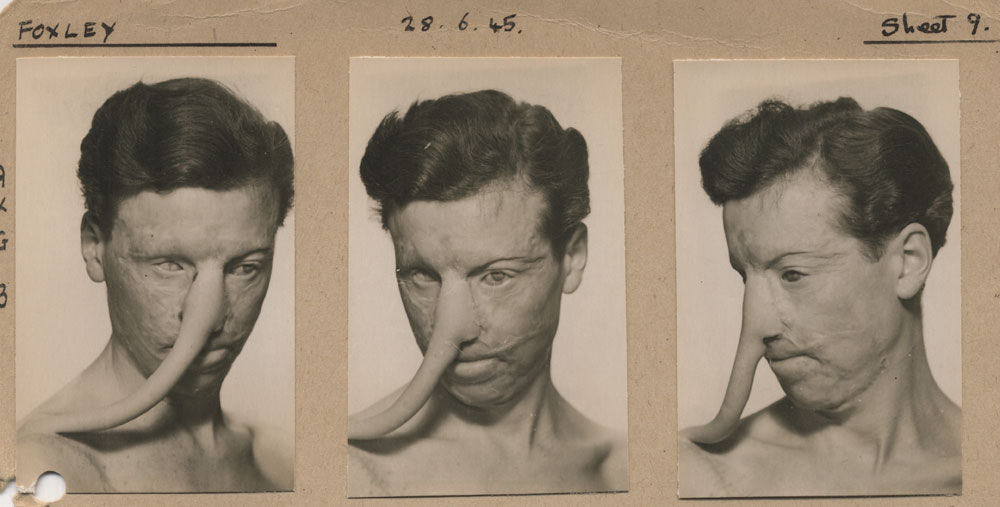

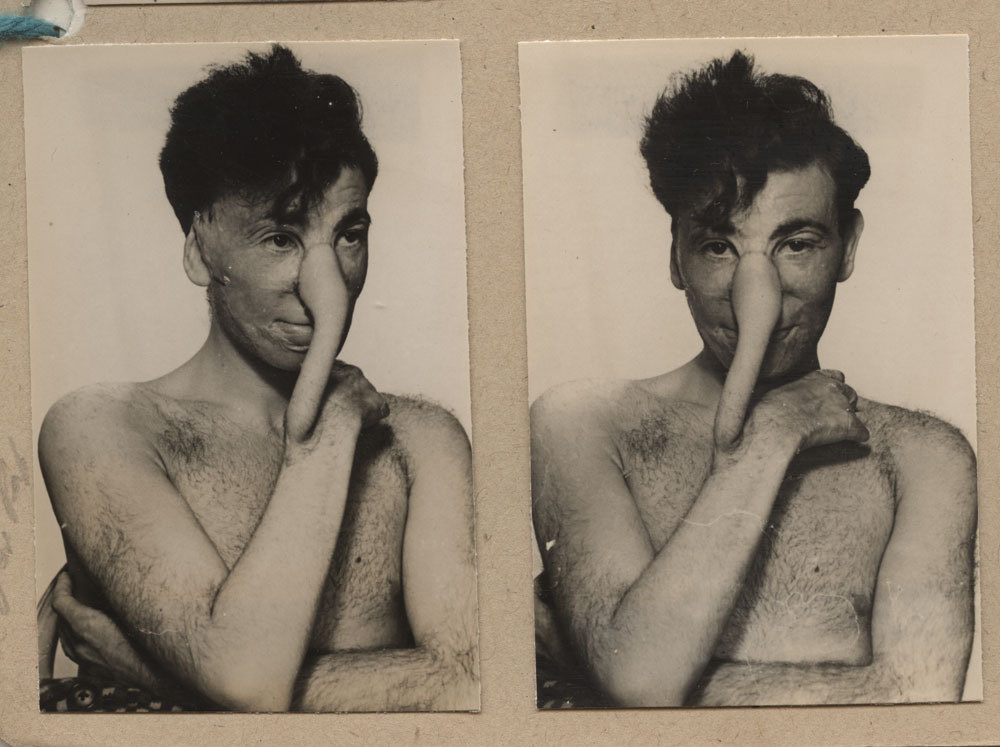

It was here in the cottage hospital that Archibald McIndoe learned to reconstruct these horrendously burnt and disfigured faces - eyelids, ears, lips, noses. And hands. It took many operations on each one of them to make whole their mutilated bits and pieces.

He did it by trial and error. At first, these were operations to return the functions of the face, so that they could open and close their eyes and their mouths. And not become blind due to constant corneal exposure.

He gave them some kind of ear (to put their glasses on) and a rudimentary pincer grip in what remained of their hands. And then subsequently fashioned the fleshy bits using tubed pedicle flaps. A sequential return of function followed by form.

It was perhaps empirical surgery. McIndoe was observing and innovating and experimenting on his own, learning on the fly. Those burnt pilots were his animal models, his surgical guinea pigs, warm bodies for practice.

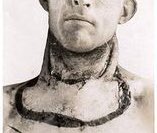

The only reference work he had was the face of Walter Yeo. Yeo was an English sailor in the Royal Navy whose face was badly burnt in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Apart from severe nasal burns, he’d lost his upper and lower eyelids.

The scar that was developing was giving him ectropion, a kind of contracture that left the eyes exposed and uncovered at all times.

The exposed cornea in ectropion is constantly irritated and unprotected and dries up. The resultant abrasions and ulcers on the cornea lead to blindness. Imagine not being able to close your eye when a fly was trying to sit on it.

Yeo was treated by Gillies, McIndoe’s surgical mentor. To recreate Yeo's damaged face, Gillies did something wildly experimental. First, he fashioned a skin mask out of flesh from the front of his chest, and then, in the second stage, attached it via tubes of flesh to his face.

The genius of the scheme was that the tubes, or pedicles as they were called, were sculpted in a way that they carried the blood supply of the flap of skin that would serve as a mask.

Gillies outlined the flap, shaped it perfectly, including slits for the new eyelids, and set it in place over Yeo's mid-face and forehead. He had to surgically clear some tissue around his nose so that the flap would fit quite nicely.

In the final stage the pedicles were disconnected and removed. With time, the flap/mask had appropriated blood supply from the part of the face where it had been transplanted. The pedicles were no longer required.

McIndoe, at East Grinstead, summoned up Gillies’ extraordinary pedicle flap and got even more creative with it. In his own words, the objective was to “make a face that does not excite pity or horror. By doing so we can restore a lost soul to normal living.”

It was a strange realm of surgical practice - to find the frontiers of blood supply of serviceable islands of skin that could then be harvested as flaps in the service of beauty. “To make a face which enabled the owner to take his place in normal society without comment.”

And McIndoe was committed that nothing would come in the way of making his boys whole again. These frightened young pilots had to believe that they were indomitable and could become symbols of grit and endurance. That would happen beyond the operating theatre.

McIndoe purposefully picked attractive nurses who wouldn’t flinch on seeing the wounds. The family members were explicitly instructed not to let even a batsqueak of a snivel weaken their resolve. Not one pitying stare was allowed in Ward III to stigmatise their wounds.

The cottage hospital got rid of the rigour and regulations of the usual ‘military’ hospital. All ranks and rules were given up. Everyone was equal. Officers and the other ranks were treated in the same wards.

Meals were not served to a timetable but whenever the patient was hungry. Beer was allowed in the wards. The patients could visit the local pubs in the evenings, in wheelchairs, pushed by nurses. On rare occasions they were even allowed to go to London, chaperoned.

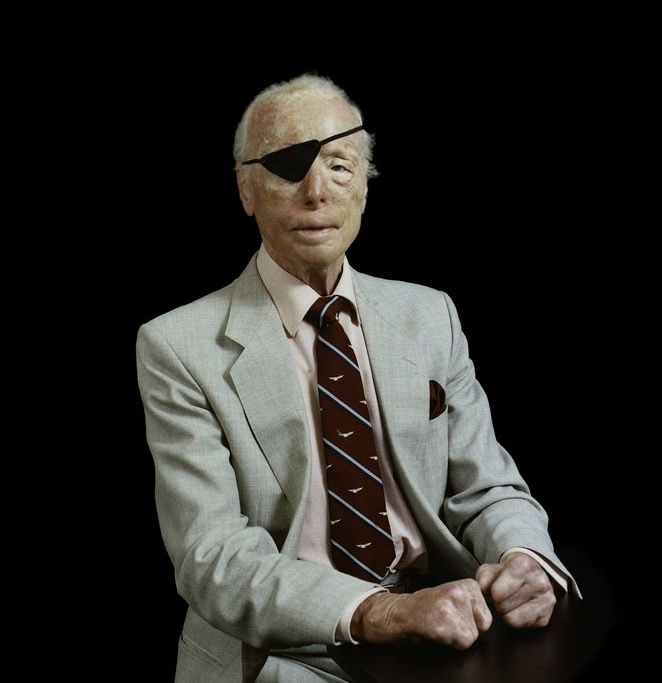

A strange sort of fellowship developed. The pedicled men became trustees of each other. It was in Ward III, during a drinking session, that the proposal of an exclusive club was bandied about.

In the words of Group Captain Tom Gleave: “… a handful us of foregathered there. Some wore the uniform of the RAF, some wore lounge suits, hastily donned after a morning spent in theatre and ward; and some wore dressing gowns and bandages.”

“The company gathered around a table, and deft hands removed the cork from a Sherry bottle. Glasses were filled and raised.”

“As the rays of the midday sun poured through the window onto that medley of costume, on a June Sunday in the Summer of 1941, a toast was drunk to the first meeting of the Guinea Pig Club.”

It was a deucedly exclusive club. Membership was restricted only to those men of the Royal Air Force who went under McIndoe’s scalpel at East Grinstead. It was famously said that to be admitted to this club, you had to be fried, mashed or boiled. And be McIndoe’s Guinea Pig.

McIndoe, not unexpectedly, was President of the club. Some of the doctors and the staff who treated the Guinea Pigs were honorary members. John Hunter, the chief anaesthetist (hailed as running the gasworks), was one of them.

Hunter had a standing wager with the guinea pigs that he'd buy them a drink if any of them got nauseous and vomited after waking up from anaesthesia. This became a Ward III ritual.

There were indeed no rules in Ward III. Someone kept a tame grass snake in his locker. Patients could go and watch surgeries from a viewing gallery. And they always accompanied frightened first timers on their trolleys into the theatre to give them courage.

Guinea Pig Harold Taubman wrote about waking up on his first day at East Grinstead: “Have a cigar” the guy in the next bed said. Some bloke in a wheelchair, his leg in a plaster cast, could be seen chasing a nurse along the ward shouting “Taxi, taxi!”

“There was a lovely sound as someone opened and poured a bottle of beer…then, the saline bath and the ceremonial shaving off of my bomber command moustache.” Horseplay and pranks were indeed a part of daily life at East Grinstead.

Sex and seduction was part of the repair of souls.

McIndoe saw the drawing power of flirtation and intimacy and the effect it had on the flagging spirit of his disfigured boys. McIndoe’s daughter Vanora Marland had this to say on the matter:

McIndoe saw the drawing power of flirtation and intimacy and the effect it had on the flagging spirit of his disfigured boys. McIndoe’s daughter Vanora Marland had this to say on the matter:

“My father wanted the best nurses and he wanted them to be beautiful and they had to be the sort of women who wouldn’t make a fuss about having their bottoms pinched. The men were young, and some of them had been deserted by girlfriends who couldn’t face their terrible injuries.”

“He thought having beautiful women around to flirt with was good for them, and he encouraged it. They had been handsome, dashing young men, and if anything was going to restore their self-esteem, it was the presence of beautiful women who were interested in them.”

The sentiment drilled into the nurses was that “it’s the war, these boys are heroes and legends, and we have to do our bit for them, whatever it takes.”

It produced a culture of social and sexual coercion that violated every code of honour in nursing. But the women, uncomplainingly, ‘did their bit’.

Off-duty nurses were encouraged to go on dinner dates with the patients. Many of them had badly burned hands, had lost their fingers. These dates often involved some amount of nursing care, i.e., feeding and helping them relieve themselves in between drinks.

It was easy to see how off-duty nursing could set alight the expectation of continuing intimate relations. Many women complied: some willingly, others reluctantly, thinking of it as necessary war work.

After sundown, there were sexual romps in the OR, in linen cupboards, sluice rooms, poorly lit passageways and in the only telephone kiosk of the cottage hospital (from which the light bulb was regularly removed).

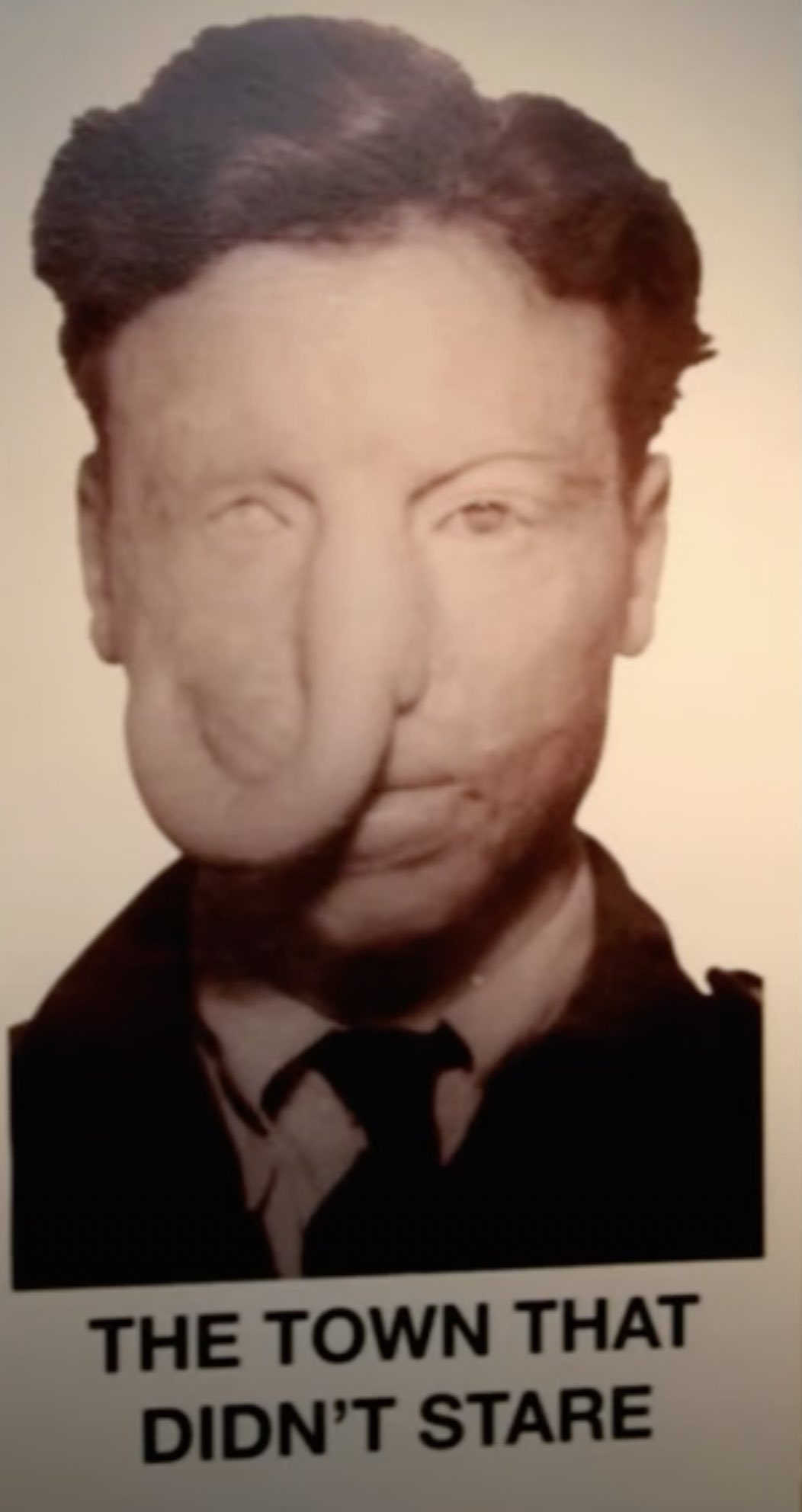

Even then, it took all of East Grinstead to return these men to normal living. McIndoe’s Guinea Pigs were affectionately received by local residents. Mirrors in pubs and shops were taken down so that the men would not even accidentally look at their disfigurement.

The good people of East Grinstead would stop these chaps in the street and chat with them. They’d take them into their homes and give them tea. The girls would invite them to dances. Not even the children would stare at them.

East Grinstead would soon be called ‘the town that didn’t stare’. An article in the Reader’s Digest in 1943 had this to say:

“They all knew that one obvious shudder might undo weeks of excruciating work at the cottage hospital. So, in East Grinstead, the most ghastly burned boy is most welcome. His face is the job of the hospital, but his will to live is a job that is in the hands of the townsfolk.”

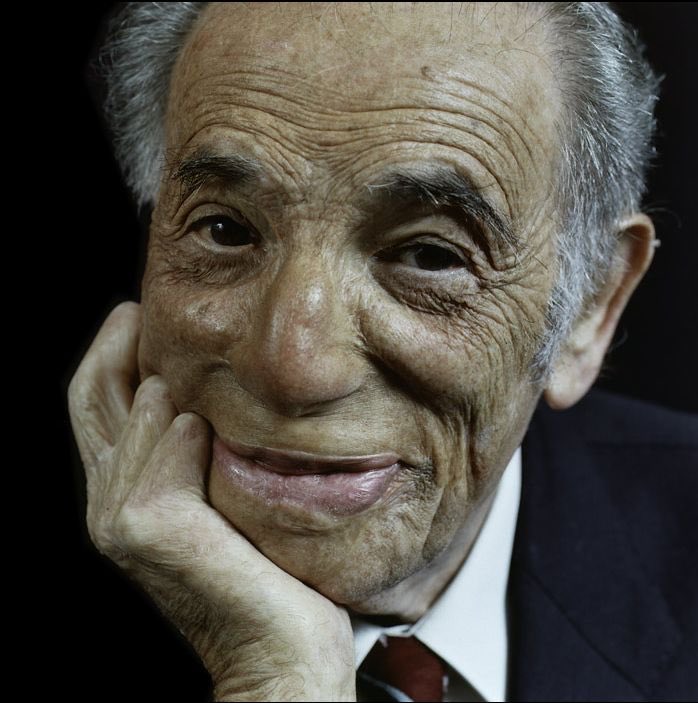

With mirth and laughter, they survived their treatment. With mirth and laughter came old wrinkles on those reconstructed faces. Every one of them lived and thrived. Got married, had families. Grew old. Everyone served as the other’s keeper.

What started its life as a drinking club grew into something completely different. Over the years, the club gathered considerable funds and became a welfare institution-cum-bank for its members and their widows.

They’d always meet once a year at their annual reunion. The last one happened in 2007, after which it was decided not to have any further meetings as the survivors were too old to show up.

At every meeting, they would unfailingly repeat what McIndoe said to them in 1944: “We do well to remember that the privilege of dying for one’s country is not equal to the privilege of living for it.’