Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required.

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Audible sample

Audible sample On Moral Fiction Audio CD – Unabridged, March 1, 2021

Purchase options and add-ons

Novelist John Gardner's thesis in On Moral Fiction is simple: "True art is by its nature moral." It is also an audacious statement, as Gardner asserts an inherent value in life and in art. Since the book's first publication, the passion behind Gardner's assertion has both provoked and inspired readers. In examining the work of his peers, Gardner analyzes what has gone wrong, in his view, in modern art and literature, and how shortcomings in artistic criticism have contributed to the problem. He develops his argument by showing how artists and critics can reintroduce morality and substance to their work to improve society and cultivate our morality.

On Moral Fiction is a must-listen book in which Gardner presents his thoughtfully developed criteria for the elements he believes are essential to art and its creation.

- Print length1 pages

- LanguageEnglish

- PublisherTantor and Blackstone Publishing

- Publication dateMarch 1, 2021

- Dimensions5.2 x 5.7 inches

- ISBN-13979-8200366545

The chilling story of the abduction of two teenagers, their escape, and the dark secrets that, years later, bring them back to the scene of the crime. | Learn more

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product details

- ASIN : B08Z2GX5FQ

- Publisher : Tantor and Blackstone Publishing; Unabridged edition (March 1, 2021)

- Language : English

- Audio CD : 1 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8200366545

- Item Weight : 3.2 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.2 x 5.7 inches

- Best Sellers Rank: #8,345,186 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

- #3,109 in 20th Century Literary Criticism (Books)

- #7,011 in General Books & Reading

- #28,141 in Philosophy of Ethics & Morality

- Customer Reviews:

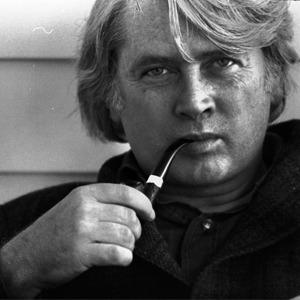

About the author

John Gardner (1933–1982) was born in Batavia, New York. His critically acclaimed books include the novels Grendel, The Sunlight Dialogues, and October Light, for which he received the National Book Critics Circle Award, as well as several works of nonfiction and criticism such as On Becoming a Novelist. He was also a professor of medieval literature and a pioneering creative writing teacher whose students included Raymond Carver and Charles Johnson.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Learn more how customers reviews work on AmazonCustomers say

Customers find the writing style eloquent and clever. They appreciate the philosophical exposition on what it means to write with serious purpose. The book reinforces the value of fiction as an art form.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the book insightful and uplifting. They say it's worth reading and thinking about. Readers also mention it's reaffirming, an important concept, and a fundamental discussion of the question "Why write?" The book is described as joyous, controversial, and a balm for homesick hearts.

"...The music spoke a message of "tidings of great joy." My soul felt enraptured with joy, a balm for my homesick heart...." Read more

"I thought this book touched on some really deep concepts and pushed me to think about my writing under a new lens...." Read more

"...solicits sympathy, irresistible, at the same time despairing and hopeful, enraged and joyous, controversial and reaffirming, and always immediate...." Read more

"...deals with the responsibility a writer takes on in being both honest with facts, true to details, and clever with words...." Read more

Customers appreciate the eloquent and skillful writing style. They find the facts and ideas well-argued and nuanced. The book provides a solid philosophical exposition on what it means to write. Readers find the author's voice sympathetic, at the same time despairing.

"...There are many great writers, in my opinion, where Beauty, Truth and Good have been used to achieve the ultimate purpose of art--redemption...." Read more

"...they proceeded to criticize, but half of the book is solid philosophical exposition on what it means to write morally good writing...." Read more

"...Gardner's writing voice solicits sympathy, irresistible, at the same time despairing and hopeful, enraged and joyous, controversial and reaffirming..." Read more

"...keeper - to read again and again - it reminds me of the higher sense of purpose in writing, the reason behind the process. Highly recommended." Read more

Customers appreciate the art value of the book. They find it moral and redemptive, reaffirming the value of fiction as an art form.

"...it for what it was, but it spoke volumes to me about the freedom of art and how it can accomplish so much more than what we can didactically or..." Read more

"On Moral Fiction: Review "True art is moral. We recognize true art by its' careful, thoroughly honest search for an analysis of values...." Read more

"Reinforces the value of fiction as an art - representation of moral concepts and value judgments in a concrete form to communicate these ideas to..." Read more

"On Moral Fiction..." Read more

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later.

- Reviewed in the United States on March 17, 2012I empathize with John Gardner and his frustration with the mediocrity of modernism, postmodernism and nihilism, and the lack of what he refers to as moral fiction in much of the arts. I have struggled with it also as a reporter/captioner; and art, as he so pedantically stated, imitates life.

Thomas Watson said, "The chief aim of man is to glorify God." To glorify God is my standard as a writer. If I deviate from that, I need to find another avocation.

I struggle with the fact that for the past thirty years I have made my living providing court reporting and captioning for broadcast television and that very few of those millions of words I have labored to accurately record have glorified God. They will burn up in the last days when God judges mankind and the world.

In the sense of structure, I did my job professionally, but the content did not glorify Him. As a creative writer, I relish the freedom to write what I choose.

As I was reading On Moral Fiction, Ecclesiastes 12:11 came to mind: "Of making books there is no end, and much study wearies the body." I grew tired of trying to understand some of John Gardner's more salient points which oftentimes made little sense to me. I found a lot of what he said to be the ranting of a frustrated critic tired of analyzing art in a mediocre world that does not care for Good, Beauty, or Truth. While I agree with his attitude toward the meaning of art and the responsibility of the artist, I disagree with some of the conclusions he drew and found them depressing.

Here is an example. I want to quote the following paragraph from page 181:

"Art begins in a wound, an imperfection--a wound inherent in the nature of life itself--and is an attempt either to learn to live with the wound or to heal it. It is the pain of the wound which impels the artist to do his work, and it is the universality of woundedness in the human condition which makes the work of art significant as medicine or distraction."

I found this quote to be insightful and uplifting. But he lost me with his conclusion when he then went on to say:

"The wound may take any number of forms: Doubt about one's parentage, fear that one is a fool or freak, the crippling effect of psychological trauma or the potentially crippling effect of alienation from the society in which one feels at home, whether or not any such society really exists outside the fantasy of the artist."

From a worldly point of view, I suppose these would be legitimate observations, but from a spiritual point of view, we know that God doesn't leave us in doubt, full of fear, a psychological cripple, or alienated; and He is more real than any fantasy that an artist could dream up, sane or crazy.

Gardner failed to instill the hope of healing and that things can be better. I believe his idea of Beauty, Good, and Truth, while a good beginning, falls short. I hope to take his idea of "moral fiction" one step further which I will expound on in a moment.

On page fifteen, Gardner gives a definition of moral as being, "...life giving---moral in its process of creation and moral in what it says."

According to Miriam Webster's dictionary, moral means "relating to principles of right and wrong in behavior."

Clearly these two definitions are not the same thing. Perhaps Immanuel Kant's philosophy is instructive in the use of the word "morality." Peter Kreeft in "The Pillars of Unbelief--Kant," The National Catholic Register (January February 1988), discusses Kant, and summarized Kant's philosophy that morality is "...not a natural law of objective rights and wrongs that comes from God, but a manmade law by which we decide to bind ourselves."

I normally wouldn't quote someone who espouses a belief contrary to Christianity, but I believe it makes my point. Morality is arbitrary depending on the situation, the culture, and religion.

If one is in Nepal, it is considered immoral to kill a cow because cows are worshipped. In our culture I consider abortion to be immoral, but according to our laws, it is not immoral to kill a baby inside a mother's womb.

In the Bible, Jesus turned over the money tables in the synagogue because the religious leaders had turned His house of worship into a den of thieves. What Jesus considered a moral and righteous act the religious leaders of his day considered immoral and sought to arrest him. Therefore the term "moral art" has an ambiguous meaning because it is too subjective.

Gardner attempted to refine "moral art" to more precisely say that it should pursue Good, Beauty, and Truth. He believed good art would embody these qualities and bad art wouldn't.

To talk about each of these words individually, Gardner discusses "Good" on pages 133 through 139, but he leaves out any understanding of God. Because man is inherently sinful, or immoral, leaving God out of this discussion came across to me as meaningless commentary.

His definition of good is described as "...a relative absolute that cannot be approached"(page 139). Because it can't be approached, he states that, "The conclusive answering of a question has not to do with the Good but with the True," and "...thus relative absolute `Truth' through reason"(page 139).

God is the ultimate source of Good and is not a relative absolute who cannot be approached. He came to earth and dwelt among us and indwells us with His Spirit--a deposit guaranteeing what is to come. It was interesting to me that when Gardner was unable to define Good in an understandable way, he then tied good to "...truth through reason."

As Jesus stood before Pontius Pilate, Pilate asked the question, "What is truth?" I do not believe it is possible to come to an understanding of "...truth through reason" at the level that Gardner intimated and Pontius Pilate asked. This type of truth, humanly speaking can't be seen, heard, or written, but through art we can "feel" His presence and capture that longing for something beyond ourselves. If Truth could be arrived at through human reasoning, the religious leaders of Jesus' day would not have sought to crucify Him.

I have found Truth to be the most elusive of the three--Good, Beauty, and Truth--because sin blocks the ability of each of us to recognize Truth. It takes a very honest person to confront his own sin and be willing to seek Truth at all costs.

Despite the limitations of knowing Truth this side of eternity, I take comfort as a writer that I am pursuing Truth that is embodied in a person and not in a relative absolute.

The third example he gave of moral art is it should portray Beauty. I recently watched the movie, American Beauty, and while it won five Oscars, I was struck by how ugly this movie was. Finding beauty in a floating trash bag, a dead bird, and perverted sexual behaviors is not my idea of beauty. Again, Gardner's use of the word "Beauty" is too subjective and therefore only partially instructive in what moral or good art should be.

I also take issue with his railing against "bad art." I don't know if it's fair to classify art as good or bad. I believe it's a matter of how redeemed we are and what our capacity is for recognizing what God would call "good art."

That brings me to what I believe the purpose of all art should be, and the most important point--it should be redemptive.

Even though most art today is not redemptive, I don't believe that means we should get rid of what Gardner would probably consider "bad art." In the end, God can use anything, good or bad, to teach us more about who He is. However, we have the choice, because we have the freedom, to choose what art we like and don't like. If someone chooses to like bad art, they should have the ability to enjoy it for what it is.

Once we start putting labels on what art is, however, we become critics (like Gardner). Once we judge art as bad, we might believe it gives us the power not to allow it or to do away with it. Once we believe we can rid the world of bad art, then who is to say that someone, given the right circumstances, would not attain the power and do away with good art? Freedom is necessary for the expression of all art, good and bad, to use Gardner's words, and I for one do not want to do away with pluralism even though I cringe at much of the art today because it is offensive.

It struck me as interesting that the authors whom John Gardner attacked in On Moral Fiction mostly have been forgotten. Bad art, if it's bad, won't last anyway, and so I don't see a need to categorize it. Pluralism is safer because then the Hitlers of the world and mockers can't take away our freedom for what is near and dear to us as Christian writers.

Continuing with the idea of Redemption, let me give an example of the power of Redemptive art--the quality that goes beyond Beauty, Good, and Truth.

In 1999, I was in Hanoi over Christmas. Displayed in the front window of one of the restaurants I frequented was a large Nativity. Vietnam is a communist country and there are many Christians who have been killed and imprisoned in Vietnam for their faith. But the Nativity scene was displayed prominently in the window as art--redemptive, full of Good, Beauty, and Truth. I may have been the only one who recognized it for what it was, but it spoke volumes to me about the freedom of art and how it can accomplish so much more than what we can didactically or academically.

Art gives us the ability to speak the Truth in a way that can reach the masses. It reassured me away from home that God was with me. Who knows what it spoke to others--but that is the catharsis of art. The individual expression in the heart of the person works out Redemption in a way that goes beyond reasoning. God is at work bringing glory to Himself, and as I said in the beginning, the chief aim of man is to glorify God.

The other piece of art I want to share comes from the same trip to Hanoi in December, 1999. It was Christmas Eve and there was a lovely Christmas celebration in downtown Hanoi. Uplifting holiday music wafted from the loud speakers over the noisy crowd. The music spoke a message of "tidings of great joy." My soul felt enraptured with joy, a balm for my homesick heart. I found myself enveloped in oneness with those around me who were there for a different purpose.

But it was the art of music that sung Truth wrapped in Beauty and Goodness, embodied in the person of Jesus Christ who brought Redemption. For me, that is the purpose of art.

I do take comfort in the fact that God promises in Isaiah 55:11, "...it [my word] will not return to me empty, but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose for which I sent it."

Perhaps someone in Vietnam heard the music or saw the Nativity and asked the question, "What is Truth? What is Beauty? What is Good?" We will never know, but I don't think it matters. We're just the bearer of what Gardner would call "moral art." We pursue the purpose for which God made us, whether we are the planters or the reapers. In the end, God's will is done and we, through Redemption, can have a small part in it.

I always like to end on a positive note, and so I will do so here. There are many great writers, in my opinion, where Beauty, Truth and Good have been used to achieve the ultimate purpose of art--redemption. The likes of C.S. Lewis, George McDonald, Madeleine L'Engle, and J.R.R. Tolkien have withstood the "isms" of the world and embodied hope in their writings that have impacted my life.

My favorite quote from "On Moral Fiction" appeared on page 204: "So long as the artist is a master of technique so that no stroke is wasted, no idea or emotion blurred, it is the extravagance of the artist's purposeful self abandonment to his dream that will determine the dream's power."

As a creative writer of memoir, that would be my dream--that what I write will not burn up in the last days but will survive into eternity. Maybe, just maybe, one person will be drawn to the Creator because of the creativity God has given me. If that be true, I will have accomplished my goal as a writer--to glorify God.

- Reviewed in the United States on December 23, 2021I thought this book touched on some really deep concepts and pushed me to think about my writing under a new lens. They talk about what it means to be a moral writer, rather than one who is simply dogmatic or capturing present sentiments. They boil down what represents moral fiction into a few different concepts. What they talk about in the book can be practically applied to your own writing. Some of the diversions were excessive, and other parts were simply lists of authors they proceeded to criticize, but half of the book is solid philosophical exposition on what it means to write morally good writing. I found it insightful. Would recommend for writers or voracious readers.

- Reviewed in the United States on August 15, 2012On Moral Fiction: Review

"True art is moral. We recognize true art by its' careful, thoroughly honest search for an analysis of values. It is not didactic because, instead of teaching by authority and force, it explores, open-mindedly, to learn what it should teach. It clarifies like an experiment in a chemistry lab, and confirms." - John Gardner

I have of late been on a kick of reading whatever I can about writing, expanding... ah, better, reviewing my sparse understanding of art and craft, the business of it. Seeking ten best lists to guide me in the right direction, avoiding pitfalls of the trite and repetitive, looking for the seminal work, the singularity. Those lists more often than not holding up On Moral Fiction as a must read. With little previous knowledge of Gardner, having only read Grendel in high school, I gleaned what I could from general sources, Okay. The title was at once revolting and enticing, expectations of a preachy diatribe, subjective, anachronistic values; then again taken in morbid curiosity as to what that proposed morality might represent, at least in its' entertainment value. It was not what I expected.

Gardner's definition of "moral" was not constrained in context of religious or cultural "morality," but rather that fiction should aspire to discover, and inspire, those human values that are universally sustaining. Values he believed innate in the human animal, values necessary for our advancement.

His statements, his very beliefs (and he always said what he believed) were disturbing to many of his people, readers, friends and followers alike, agreed or disagreed, often displayed to their exasperation... Poor brilliant Gardner! What will he say next? Yet, he's described as warm and generous with his time, willingly engaged in debate. Against the grain of the old adage - It's not what you say that counts; it's how you say it. To Gardner it was indeed what you say that counted, and it better be honest. The `what' was the construct, and vice versa. He longed for "a return to the discussion of rational morality that his (Sartre's) outburst interrupted."

I typically skip introductions, forewords and prologues. I'm glad I didn't. Lore Segal's introduction is a far cry from the typical patronage, trivial and uninteresting anecdotes, mushy accolades raising the author to deity sprung full grown from the head of Zeus. Instead, taking the occasion to point out positions faithfully held by Gardner proven flawed by more than thirty years of inconvenient history. Specifically his attitudes toward modern art and music, and predictions of their ultimate demise, a natural selection of sorts, victims of their own hollowness and disingenuousness, their celebration of the trivial and nihilistic, "the freak", victims of their own immorality.

Her personal relationship with Gardner gives her a special insight into his beliefs about what constituted moral art, and as importantly what didn't, to which he would rail, captured in his words - "Honest feeling has been replaced by needless screaming, pompous foolishness, self-centered repetitiousness, and misuse of vocabulary!" Does that sound mad, or is it just me? (I added the exclamation mark, it deserves it.)

I will not be so presumptuous to put in a few words what Gardner expounds on. But I will say Gardner believed it was an artist's, and critic's, responsibility, even obligation to society and its' betterment that they zealously pursue morality in the process and the product. "Good art is always in competition with bad art." - J.G. Moral art exerts influence on society, proposing, holding up models of behavior. The artist has intuition in place of scientific hypothesis, but it has to be as carefully examined within integral laws and tradition, "the morality of art... is far less a matter of doctrine than of process." -J.G.

Gardner's writing voice solicits sympathy, irresistible, at the same time despairing and hopeful, enraged and joyous, controversial and reaffirming, and always immediate. Mind you, it is not to say I could swim in the depths of his philosophy, missing much nuance, but his ideas, skillfully argued, guided and textured, will take you as far you can or want to go, whether limited by capacity or disagreement. There is something for everyone, artist, critic and enthusiast.

If Gardner were alive today he would very surely dismay with society's trend toward the devaluation, even demonization of critical thinking. The state of personal communications, bits (a descriptive he would have certainly got a kick out of) of data exchanged poorly formatted, the rise of a didactic morality happier in provocative sound bites and expedient answers: Instead of one welcoming of a thoughtful, and civil, discourse aspiring to genuine solutions, to truth itself. John Gardner we miss you, and your brutal honesty.

Xavier Morrison 8/15/12