Canadian Jeremy Hansen, right, is one of the team members for the Artemis II mission, commanded by Reid Wiseman, front. Victor Glover, top middle, and Christina Koch, left, round out the crew of four.Josh Valcarcel/NASA/JSC

More • Graphic: Artemis II explained • Interview: Jeremy Hansen on the mission • Timeline: Canadian milestones in space

Canada’s Jeremy Hansen is moonward bound.

The 47-year-old astronaut and CF-18 pilot has been selected to join Artemis II, the first mission to carry humans around the moon in more than 50 years.

No Canadian – no one from any country other than the United States – has ever ventured so far from home, gazed at the moon’s far side or had the chance to take in Earth as a separate world traversing the dark void of space.

Now Col. Hansen is on course to do so as a mission specialist on Artemis II. First selected to be an astronaut in 2009, he will be taking Canada’s space program to new heights when he sets out on a lunar flight as early as November, 2024.

“It truly is humbling to think about this opportunity being presented to me as a Canadian,” he said after his selection was announced Monday at NASA’s Johnson Center in Houston, Tex. “I’m just so proud of Canada for having the vision, the can-do attitude to step up and contribute and to put us in a position to do something this big with our American allies and partners.”

François-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, who participated in the announcement, said the country’s involvement in the mission was “about investing in the future.”

“Let’s inspire the next generation to reach for the stars,” Mr. Champagne said.

Three Americans will be making the trip with Col. Hansen. Gregory Reid Weisman, 47, will be the commander on the flight. A former chief of NASA’s astronaut office, Mr. Weisman spent 5½ months on the International Space Station in 2014. Pilot Victor Glover, 46, and mission specialist Christina Koch, 44, have also logged missions aboard the station.

Artemis II will be Col. Hansen’s first flight into space. It could be regarded as a fitting reward for his perseverance – he has been waiting almost 14 years for a mission assignment.

Born in London, Ont., he was raised on a farm in nearby Ailsa Craig and attended high school in Ingersoll. He became an air cadet at age 12 and by 17 had earned both his glider and private pilot licences through the program.

Mr. Hansen gives a tour of a Canadian Space Agency test facility to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his daughter, Ella Grace, in 2019.Christinne Muschi/Reuters

At 18, he joined the Canadian Armed Forces and remains an active member. He attended the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston and graduated top of his class in 1999.

He went on to earn a master’s degree in physics the following year, for research related to satellite tracking. He later trained as a CF-18 pilot and was a combat operations officer at Cold Lake, Alta.

After he was selected for the space program, he said he could not remember a time when he didn’t want to be an astronaut or did not dream of looking at Earth from space.

He is married with three children.

Like his crewmates on Artemis II, he has spent years training in Houston and elsewhere as part of the ongoing cycle of expeditions to the International Space Station.

Now he will help start a new chapter for the astronaut program, not just in Canada but in the U.S. and 21 other countries that have signed on to the Artemis program and the goal of establishing a long-term presence on the moon.

The far side of the moon looms beyond the Orion spacecraft last November during the Artemis I mission.NASA

Unlike the Apollo program of the 1960s and 70s, when the United States temporarily committed a massive budget to besting the Soviet Union in a race to get astronauts onto the moon, Artemis is taking a modular and multi-pronged approach that advocates of the plan say will expand lunar exploration much further than Apollo was able to achieve.

For example, when the first Artemis moon landing occurs, with Artemis III, it will be near the lunar south pole, a location that is technically more difficult to reach than any of the Apollo landing sites, but more interesting because of the potential presence of ice reserves in the soil.

The lander will not travel with the crew to the moon. They will instead transfer to the lander in lunar orbit.

Since that lander is still being developed by the American spacecraft manufacturer Space X, Col. Hansen and his crewmates will have no such option on their flight. But the Artemis II team is expected to have their hands full proving out a spacecraft that has never flown with people on board.

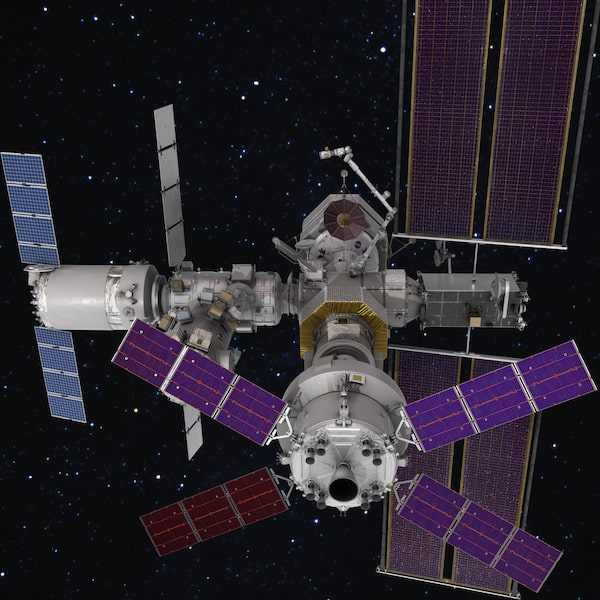

The stage was set for Col. Hansen’s participation back in December, 2020, when Canada agreed to be a partner in the lunar initiative and supply hardware for Gateway, a moon-orbiting space station that will serve as a platform for lunar science and a home base for expeditions to the surface.

Canada’s principal contribution to Gateway will be the Canadarm III, an AI-powered descendant of the robotic arm aboard the International Space Station. It is currently being built by MDA Corp. in Brampton, Ont.

An artist's rendering of the Gateway space station, including Canadarm III, a new model of the Canadian-made robotic arm.NASA

Lisa Campbell, president of the Canadian Space Agency, watches April 3's announcement from St. Hubert, Que., with ex-astronaut Marc Garneau.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

The effort is an indication of how the lunar program has grown as a Canadian priority, with contracts awarded to industry partners to supply additional technology and a lunar rover over the next several years. “We’re bringing along the country,” said Lisa Campbell, president of the Canadian Space Agency.

The vehicle making a return to the moon feasible saw its debut last year with Artemis I, a 25½-day test flight that sent an uncrewed Orion capsule into a long, looping orbit around the moon before returning it to Earth for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

In addition to providing the first demonstration of NASA’s mammoth Space Launch System, or SLS rocket, Artemis I was a crucial test of the heat shield built to protect the Orion capsule and its crew from the searing temperatures encountered during re-entry.

Its success has cleared the way for Artemis II.

The next mission of the series and the first to carry a crew around the moon will be shorter in duration – approximately 10 days.

After launching from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the spacecraft will perform a series of burns to transfer from a lower to a higher orbit. Before leaving Earth’s orbit altogether, the astronauts will use a spent propulsion stage to practise manoeuvres that will be required in the future when Orion docks with another spacecraft.

Once en route to the moon, the mission will focus on human operations and life support as it traces a long, narrow figure 8 around Earth’s satellite. At this point, Col. Hansen and his crewmates will be treated to the sight of Earth, by then almost 400,000 kilometres away, with the moon in the foreground.

The view will be similar, though not identical, to the one experienced by astronauts on Apollo 8, who were the first to fly around the moon before returning home in December, 1968.

From a mission perspective, Artemis II will mainly focus on what is going on inside the Orion module, but scientists are anticipating the opportunities that the program’s longer-term focus on the moon will bring.

Gordon Ozinski, a professor of planetary geology at Western University in London, has already been working with NASA astronauts who may be on subsequent missions to explore the lunar surface.

“It will enable us to do so much new science on the moon,” Dr. Ozinski said. “Apollo is a testament to that. We are still looking at the samples they brought back almost 55 years on.”

A future Artemis mission will include a second Canadian lunar astronaut, who will fly to Gateway as part of Canada’s contribution. As the program unfolds into the 2030s, it remains to be seen if opportunities will arise for Canadians to walk on the surface of the moon.

Canadian Astronaut Marc Garneau onboard Challenger in 1984. Mr. Garneau was the first Canadian astronaut to go to space and he conducted a series of space science, space technology, and space life science experiments called CANEX-1.

For now, attention will be focused on Col. Hansen’s voyage, a leap that recalls other big milestones for the country’s astronaut program, including the October, 1984, flight of the space shuttle Challenger, which saw Marc Garneau become the first Canadian in space.

When Mr. Garneau found out he was to be the first to go in March of that year, he had only been an astronaut for three months. “It happened at lightning speed,” he told The Globe and Mail. “It suddenly made me realize I had big weight on my shoulders because, first of all I wanted to do my job, which was to do some experiments in orbit. And secondly, I wanted to make Canadians proud.”

Col. Hansen, like his crewmates, has had more time to consider the public attention that will come as training and preparations commence for Artemis II. And given the nature of this mission, it’s all but guaranteed that the attention will be there.

“This is a major, major step in Canada’s human exploration program because, let’s face it, Canada will be the second country to have an astronaut go on a lunar mission,” Mr. Garneau said. “And that is an extraordinary privilege.”

Anatomy of a moon rocket

While similar in appearance to the Apollo capsules that first carried humans to the moon in the 1960s, the Orion crew module is 50% larger by volume and can carry up to six crew members. Together with its European-made service module and an interim stage for reaching high Earth orbit, the crew module sits atop NASA's heavy- lift rocket called the Space Launch System.

SLS

ORION

Launch abort system:

Propels Orion capsule to safety

Service module

98.2 m

Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage

(ICPS)

A look inside

CREW MODULE

Crew: 2-6

Diameter: 5 m

Height: 3.3 m

Mass: 8.5 tonnes

Heat shield: Largest

of its kind ever built

To the moon and back

Between liftoff and splashdown, the four crewmembers of the Artemis 2

mission are expected to travel nearly 800,000 km in about 10 days

Apogee

raising

burn

Trans-

lunar

injection

3

Earth

Splashdown

8

Launch

Outbound

transit

4

ICPS Earth

disposal

7

Crew

module

separation

Return

flight

Outgoing trip

6

Return trip

Moon

Orion: Crew and

service module –

can transport four

humans further into

deep space than

ever before

Lunar

flyby

5

Lift off from Kennedy

Space Center into

low Earth orbit and

booster separation

After system check

service module fires

to place Orion on

lunar trajectory

Lunar flyby will take

Orion just over

10,000 km beyond

moon’s far side

Service module

separates prior to

re-entry into Earth’s

atmosphere.

Two burns raise the

spacecraft to a high

orbit followed by

ICSP separation

Outbound transit

to moon takes

four days

Return flight will rely

on Earth’s gravity to

pull capsule home

Heat shield protects

crew module during

first part of descent

to Pacific splashdown

ivan semeniuk, john sopinski and murat yükselir/the globe and mail,

SOURCE: REUTERS; GRAPHIC NEWS; NASA

Mr. Hansen, shown in 2021, gave an interview with The Globe and Mail about his role in the Artemis II mission and the challenges ahead.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Interview: Moon talking with Jeremy Hansen

What will you be doing during the mission?

The crew and I have been talking about that. We haven’t yet developed specific roles. We know we’re going to have a lot of demands on this mission and we’re going to have to figure out who’s going to do exactly what to get everything done. We know, for example, that the first 18 hours are going to be extraordinarily busy. We are going to be flying the vehicle manually for the first time.

What does that mean from a training perspective?

We anticipate training will start in earnest in June. It’s not so much a training flow as it is a test and development flow. This vehicle has never flown with humans on it. There’s no textbook to open up and read. We have to figure this out with the team.

As a fighter pilot and astronaut you’ve had plenty of time to think about risk. What changes about your perception of risk now that you’re part of a first human flight?

It is a different risk posture, definitely. But I have such enormous faith in this team and how we work through risk. I think the Artemis I launch scrubs [in August and September, 2022] are a tremendous demonstration of that. We’re willing to take risks, but they’re going to be calculated risks. And when we don’t understand something, we’re going to pause and figure it out.

How did your children react to the news that you were selected for the mission?

The part that was really fun for me was just how authentically excited they all were for me. This is a lifelong goal for me, and they really care about that. That meant a lot to me.

What are you most looking forward to on the flight?

What I’m most looking forward to is seeing Earth from the other side of the moon. I’m going to be a very fortunate Canadian to look out a window, see the moon in the foreground and our beautiful planet beyond it. And I hope for the entire crew that we’re going to be hugging each other and that that is just absolutely incredible.